Using informatics to study Pluto’s chemistry

NAU Informatics major Jason Libby is developing computer software to help solve a mystery on Pluto’s surface.

It only seems fitting that Jason Libby is working on a project involving Pluto. After all, Jason Libby grew up in Flagstaff, Arizona, where Clyde Tombaugh of Lowell Observatory discovered Pluto in 1930. Tombaugh spent months patiently looking at photographs of the night sky before he found the planet. Fast-forward almost a century, and today, Libby uses molecular chemistry simulations to develop digital models of what is happening on Pluto’s surface.

Libby uses the power of big data—or informatics—to study Pluto. In May 2022, he will graduate with a bachelor’s degree in Informatics and an emphasis in Bioinformatics. “When I started at NAU, I was interested in a lot of different things within STEM. I really liked math, and I really liked biology, and I really liked computers,” says Libby. “The Informatics program stood out to me because I was able to branch out into all of those things within that one major. It’s given me a lot of freedom in terms of what research I can do and what I can learn about.”

Libby didn’t set out to study Pluto; he just wanted research experience. He heard from another student that Gerrick Lindberg, associate professor of physical chemistry, was working on projects he might be interested in, and pursued the opportunity. When he was a sophomore, Libby’s first project involved simulating cell membranes and antibiotic ionic liquids. He started the Pluto project as a junior with funding from the NAU/NASA Space Grant.

The New Horizons spacecraft flew by Pluto in 2015 and sent back intriguing photos of the planet’s surface. Now funded through a Hooper Undergraduate Research Award, Libby is writing software to answer some of the questions raised by the New Horizons flyby. Libby is working with a team of researchers, including Lindberg from NAU and astronomer Will Grundy from Lowell Observatory. “I’m writing chemistry software really, and my hope is that I can create something that researchers in my group after me can use too, whether it’s in the context of Pluto or other subjects,” says Libby.

One mystery the team is trying to solve is why there appears to be fluid moving on Pluto’s surface at a brutal -387° Fahrenheit. “It’s kind of perplexing that there could be liquid there at that temperature. The hypothesis we’re looking at is that there may be a mixture on the surface called a eutectic mixture, where because two things are mixed together, they can be liquid at a lower temperature together than individually,” Libby explains. “That sounds more complicated than it is; salt and ice are examples. When you put salt on ice, it melts at colder temperatures. Or anti-freeze—things like that.” Libby explains they are looking at hundreds of different eutectic mixtures at extreme temperatures, which is difficult to do in the lab.

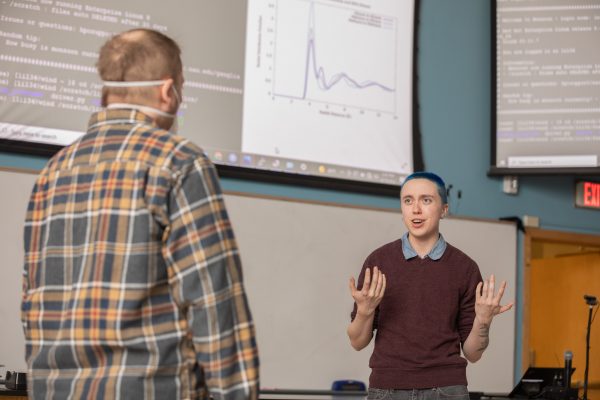

As Libby writes code on the behavior of chemicals on a faraway dwarf planet, he is gaining experience not only in computational research but also in what it means to be involved on a research team. Libby attends the weekly research meetings, gaining insight on how to present data from other researchers and guidance from the mentorship of Lindberg and Grundy. Libby explains that Lindberg offers suggestions on projects and helps him maintain steady progress. Grundy provides direct insight on Pluto and information on New Horizons data. Libby has been working in computational research since his sophomore year, and that has boosted his confidence. “I’ve gotten so much more practice than I would have on skills like presenting, on writing code, and modifying my own code,” he says. “It’s professional experience I just wouldn’t have gotten otherwise.”

After graduating, Libby will take time to reset and spend some time away from the computer. But the pull of research will draw him back. “I definitely want to keep doing research. I find science inspiring, and I like the puzzle of figuring out things that nobody really knows yet.”