NAU’s Elder Cultural Advisors program was established more than 25 years ago to provide students with cultural and spiritual support from Native American Elders. This innovative program has been an essential component of NAU’s mission to serve and support Indigenous students. Working one-on-one with students, Elders help them maintain cultural continuity and balance Native cultural traditions with university life by providing traditional knowledge and teachings on campus. The Elders do not hold faculty positions and are funded through private gifts and grants.

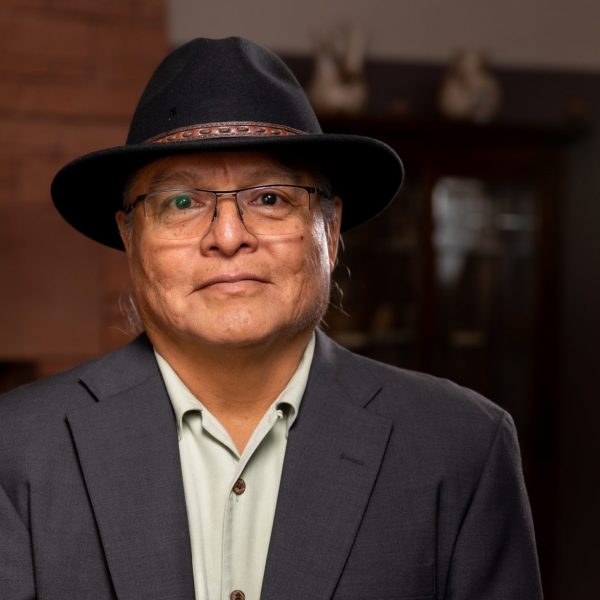

Elder Viki Blackgoat, Diné, has been part of the program for two years and talks about her experiences in this Q&A. You can also read about the other two Elders, Paul Long, Diné, and LeRoy Shingoitewa, Hopi.

What is your tribal affiliation and clan information if you care to include it?

I am of the Bitter Water clan born for the Many Goats People. My maternal grandparents are the Salt clan and my paternal grandmother was of the Honeycomb People.

Tell us a little about your background—where and how you grew up.

I was raised deep in Navajo country, out at the Big Mountain area. My father was a medicine person. He was a healer, a chanter. My mother was educated to the eighth-grade level. When her parents died, she moved back and took up the traditional lifestyle. She married my father, and we, the children, were raised with traditional teachings and values. They taught us a lot of the Navajo belief system, values, morals, practices, and language.

At first, she didn’t allow my sister to go to school, but when I came along, six kids later, she decided that for us to be versatile and adaptable, we needed to be able to function in mainstream America as well as the traditional Native lifestyle.

I started in a boarding school that was built there near the trading post. So roughly 18 miles from our home was the boarding school for kindergarten and first grade.

And then, after that, we had to find a new place in another school that could accommodate second grade on up. When that happened, my mother placed me in the Flagstaff Unified School District, and I boarded at dorms. I was the youngest boarder there. It was four or five hours from home, and it meant being able to go home maybe only once a month if I was lucky.

When I was in high school, I came upon some college information that belonged to my brother, who had gone to boarding school in Massachusetts. We were doing our annual suitcase cleaning. We each had a foot locker-type setup. And my brothers were both gone that summer, so I cleaned out their foot lockers and discovered all this college material in one of my brother’s foot lockers and unearthed a bunch of information on colleges. One of them happened to be Dartmouth College, so I applied. And that’s how I got into Dartmouth.

Dartmouth had recently gone co-ed, from an all-male student body, so the numbers were still very skewed towards male students. And so when I got there, it was very male-dominated. And it was a little much for me, so I took a couple years off, started a family, and went back as a slightly older student. And when I went back, family was a priority, but education was a priority, too, so I had to figure out a way to handle both, so I just went straight through.

Instead of taking summers off or a quarter off here and there, I just went straight through and graduated in a year and a half. I got a bachelor’s in sociology with a minor in education.

Then I concentrated on family, and we got to travel a little bit. I worked at Northfield Mount Hermon School, which was the largest boarding school on the Eastern Seaboard, and worked there in various capacities as advisor to the Native students, as a coach, as a dorm parent, and as a campus dean.

We moved back to Flagstaff in 2002, I believe it was, after my children graduated from high school. That was also spurred by the passing of my mother. My siblings asked if I could move back, and so I did.

What would you like the campus and community to know about your story?

My mother and my father used to say that we—as Bitter Water people—in the ancient stories, the stories tell us that Bitter Water people were teachers and educators and instructors. So I sort of went into teaching because of that.

When I worked in Massachusetts, I worked as a preschool teacher. But I also worked as a consultant to a lot of the regional colleges and universities that had Native American students in attendance. A lot of those students didn’t have the close support of another Native Elder or adult.

So I would go visit them every couple of months, just to support them and be with them and take them out to dinner or whatever, and recognize the achievements that they attained during the time that they were in their schools. So that they had an adult figure or a parent figure who would come in, check on them, and check their progress. It’s the kind of work I love. And I feel like I’m still doing that kind of work here as an Elder.

Taking classes and going to college can be really draining. And you needed some relief. You need a way to relieve some of the stress and the tension.

So when I work with students at NAU, I offer workshops like crocheting or knitting or weaving and beading and sewing. Things like that that not only teach another skill but actually kind of relaxes you. The academic side of your brain relaxes and sits back a little bit and takes the foot off the gas pedal, and lets another section of the brain work. It’s just calming in its own way; it’s less stressful and more relaxing and calming and allows their creativity to come through.

When we talk about k’e’ and generosity and this reciprocity, we put a lot of emphasis on our connections to other people and other life forms.

What would you like the campus and community to know about your culture?

K’e’ is referring to your relationships, your ties, and your connectivity to people around you and to life around you. Relationships are very important. As families are long distances apart on the reservation, it’s important to keep in mind the welfare of people so that when you know somebody is alone or when you know somebody is in a particularly remote place, you go to visit them and check on them. It’s always a good thing to bring along bags of food or just things that are kind of hard to acquire. And now, for instance, I’m sure the roads are really impassable at this point, or not all families have vehicles that can weather the snow.

And mud comes shortly after snow. So it’s just nice, if you have the ability, to go out to help and check on people. It’s nice to bring along some essentials that they may be needing. Maybe the sheep don’t get out or can’t get out in the snow this deep, so to bring along a couple bales of hay is just always helpful and thoughtful and very much appreciated.

And if you take care of those lines of relationships, you are taken care of. So you take care of people. They take care of you. And so when we talk about k’e’ and generosity and this reciprocity, we put a lot of emphasis on our connections to other people and other life forms.

What do the Native American Initiatives’ values of Relationships, Respect, Responsibility, and Resilience mean to you?

We occupy a certain space in this world. And we need to recognize that we’re responsible to those who dreamed us into this world, who wished us into this world. By recognizing the importance of those figures and by respecting them and honoring them, we need to be reverent and remember every day that people who came before us didn’t have it so easy.

We need to remember their resilience, spirit, and can-do attitude. And then, sometimes, it was not a can-do attitude that they needed. They needed a must-do attitude because they were praying for a good future for their children to survive, and to ensure the future of their grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

To maintain an environment that is healthy and vibrant, you’re ensuring a good future, a solid future for your own children and grandchildren.

What do you hope to achieve as a Native American Cultural Center (NACC) Elder?

My workshops always turn out students, but occasionally some adults will wander in. And they’ll say, “Is it OK if I participate?” And everybody is welcome in my workshops. It’s a time to be together. It’s a time to talk and communicate and share.

And sharing, I think, is so important. There’s so much to share in terms of our stories, in terms of the language, in terms of culture and beliefs. And a lot of times, it’s just sharing from the heart, just being together.

And I want not only students but adults of this community to see that Elders and students aren’t so different, that many of us Elders remain vibrant and active and want to contribute in some way. And this is my way of contributing. This is my way of sharing, and I hope people take me up on it. What I try to serve up is soul food.

What challenges are facing Indigenous students?

Oh, there’s so many things. When I was a student in high school, I noticed a lot of bullying and racism, prejudice, and discrimination against people of color. And it still remains so to this day in many ways, in many forms. It just seems like a lot of the challenges that students have to deal with have multiplied and almost transformed into new challenges.

Why is NAU’s land acknowledgement important for the university?

I think it’s important for the community to recognize that the place they live may have had a different identity before they arrived or before their own ancestors arrived here and to recognize that and hopefully respect that. I think that land acknowledgement helps people begin to think about what this land used to be before the town was established.

If they would take it a step further, they could actually see, or begin to see, and begin to unravel what this mountain means to Indigenous peoples that live here. We don’t need to build structures, buildings, if you will, to encompass or contain a religious place where we can practice our religion.

As Indigenous people, we recognize that certain landforms are homes to deities and sacred beings and important resources. And I wish people would understand that the Peaks here is such a landform; it marks the Western end of our homelands. Along with three other mountains to the east, to the north, and to the south, it forms the physical map that we, as Diné, were told was our homeland, and we needed to take care of it.

She is a female spirit, this mountain. We depend on her ability to negotiate important things and resources for us as living beings—not only human beings but animal forms, bird life, reptiles, and insects. This mountain negotiates everything from water to the heat that we get and the runoff, the water resources that she’s able to capture, all that determines our health and her own health. If we don’t take care of her, we’re certain to suffer some drawbacks, some losses. That has implications for the future.

Please provide ways you are inspiring cultural stewardship.

I garden in my backyard. And I call myself a rogue gardener sometimes. I take seed that is older, or I’m having trouble getting it to germinate, and I just toss it out. Either the birds will eat it, or animals close to the ground will find it. Or it’ll sprout and become part of the wild vegetation.

And it should make for good foraging for people who forage for wild foods. So if somebody finds a patch of rough asparagus out in the woods someplace, that was probably me. And just a bunch of flowers that look like they just don’t belong in a certain space or whatever, it’s possible that might have been cast from my hands.

Can you share a specific moment when interacting with an NAU student as an Elder that you find memorable?

I think when I taught weaving for the first time. It wasn’t Navajo-style weaving. It was actually an old folk art that I started playing with. I do what we call twining. And the results were so awesome that I decided I’d continue that instead of Navajo-style weaving because Navajo-style weaving was very physically taxing for me. This is a type of weaving that allows me to stand if I want.

It’s an old folk art out of the South. Women would tear down all their linen that they weren’t using anymore. They would deconstruct it and strip it all out. They would use the material for weaving rugs so that the old sheets or the old shirts, even clothes, could be used for one more thing before being tossed out into the garbage pile. I just take sheets and fabrics that I find to be durable and long-wearing.

Twining is basically twisting fabric in between the warp strings. It gives an arrow-like pattern and can result in really dramatic results and just really pretty rugs.

The students get a kick out of it when I tell them that I’m appropriating old Southern art. But I see the possibilities. And that’s one of the reasons why I took to twining because I wanted to see what I could do to push it in terms of pictorial art.

One of the things that I try to stress to students is, “Find something you enjoy. Find something that you really excel at that just comes to you naturally.”

What is your family history with NAU?

This is my second year with the Elder program. And my own history with NAU is that my brother—I have two brothers that were born before me—the older of the two went to NAU for his college education.

After I finished Dartmouth, I would make the point of visiting home every summer. So we’d drive back from Massachusetts and spend time here. And I’d live with my sisters, or I’d bunk at a relative’s house, or on the NAU campus if I could get the housing there. And I would take summer classes. And that’s how I gained my master’s degree in Education with an emphasis in children’s literature.

What is your favorite part of being a NACC Elder?

Spending time with the students, whether it’s working on projects together or just sitting and sharing a meal. They’re always so thoughtful. They’re always asking if they can get me something to drink or eat. Just spending time with students, telling stories. I love trying to make them laugh and try to shock them a little bit.

Despite all the horrible stuff that’s happening in the world, I really do feel a sense of hope from these kids.

Is there anything else that you would like to share?

I love a good story. I can’t tell jokes very well, but I enjoy good jokes. In Navajo, too, humor is very valued and highly prized, and so I’m always disappointed that I can’t hold onto punchlines very well. But I love it when somebody shares a good joke with me.

I believe that students are our future, and we need to invest our time and our patience with them because somebody, somewhere back in our own histories, somebody gave us time. Somebody gave us their patience and taught us something important. And we need to remember that and try to pass that on.

More often than not, I am very optimistic and hopeful for our future and for the future of our children. I’m reminded that, yes, even though I may get down some days, I meet enough students that blow me away with their imagination and their words, their stories, and their own hopes and dreams. I’m inspired by them, but I try to aspire to be there for them in case they need to share a hard moment or to celebrate a moment. I just try to be available and be present for them when they need me.