NAU’s land acknowledgement:

Northern Arizona University sits at the base of the San Francisco Peaks, on homelands sacred to Native Americans throughout the region. We honor their past, present, and future generations, who have lived here for millennia and will forever call this place home.

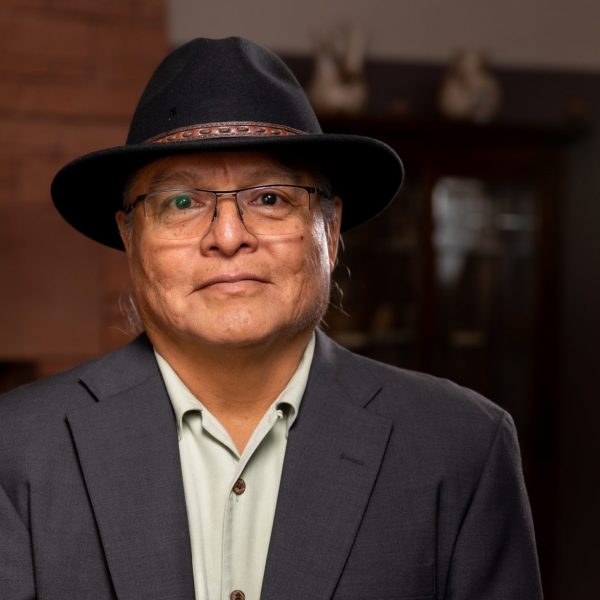

Ron Lee discusses place and identity

Sitting in the story room of NAU’s Native American Cultural Center, the San Francisco Peaks framed in the window, Ron Lee, senior development director for NAU’s Office of Native American Initiatives, explains that his identity as a Navajo/Diné man is rooted in his ancestry and the land he was raised on. To introduce himself, he begins with his name and then situates himself within his four family clans.

“Our holy people endowed us with our clan system and it is how we present ourselves and relate to one another,” Lee explains. “So, my English name is Ron Lee, but I also have a true and spiritual name, a name that I use only to commune with the natural world and the holy people. I represent the Salt Clan (Ashiihi), an inheritance from my mother, and from my father, ‘the people who walk about’ (Nakai Dine’é). I also inherited my maternal grandfather’s clan, ‘the black streaks below the rain clouds’ (Tsinaajini), and my paternal grandfather’s clan, ‘the people who live near the water’ (Tabaahi). My clans are my identity. They have everything to do with the decisions I make on a daily basis, and tie all of our generations together.”

Lee grew up in Teesto (which means ‘large cotton tree’ in Navajo), a small isolated area in the southwestern Navajo Nation. The experiences he had there, he said, were foundational to his understanding of his place in the natural world.

“When I first came to acknowledge my surroundings as a youth, the first time that I really understood and knew where I was, was among animals. I was among sheep, horses, donkeys, cattle, chickens, and I just loved being out there. I was brought up in that environment, taking care of animals and learning how to live off the land. I was lucky to get exposure to the Navajo language and to take care of the land and the animals. I have that knowledge.”

Lee was instrumental in developing NAU’s land acknowledgement in 2018. In the process, he calculated that in addition to the Navajo, more than a dozen Tribes in the area consider the San Francisco Peaks a sacred place. So it was important that the land acknowledgement be inclusive of all Tribes that have a connection with the land where the university sits.

Lee is here today to explain what the Peaks mean to the Diné. He tells a story of origin, identity, and culture.

Land acknowledgement is nothing new for Indigenous Peoples, but the concept is new from the Western view. The land is what makes us Indigenous; our creation stories tell us that we evolved from the land. Every day, we acknowledge our ancestral lands and what it means to us: we have a direct relationship with the natural world. We call the earth our mother and the sun our father. This relationship is in our stories, prayers, and songs.

In his own words

Shortly after I started working at NAU in 2017, I said it would be good to have a land acknowledgement so that Indigenous Peoples from this area can acknowledge themselves and be acknowledged. Growing up, I went between public and boarding schools on the reservation and was not taught about Indigenous history. In American history textbooks, when it came to learning about Indians in America, I recall the mentioning of Indians along the east coast and more or less as “the enemy.” In fifth grade, while reading about the Boston Tea Party, it was mentioned that the Indians or savages had something to do with dumping tea in the water, but I couldn’t understand why Indians would do such a thing—I was confused. Of course, American Indians, or Native Americans, really had nothing to do with that.

Other than that, we were erased from history.

Why? It wasn’t until I got into graduate school (the Master of Public Administration program) at NAU that I started learning about our history in America. What I learned as an adult came as a real shock to me and I’m still recovering from it. I don’t think we, as Indigenous Peoples, will ever fully recover from this historical, collective, and intergenerational trauma that we have been through. Imagine being a citizen of your own country and having someone from the outside come into your country and tell you, “You are not a citizen!” In a nutshell, that’s basically what happened.

Therefore, having a land acknowledgement at NAU would give us an opportunity to learn about our true history in America. To learn the truth and acknowledge not only the good—but also the bad and ugly—only makes us a stronger and unified nation. Land acknowledgement is nothing new for Indigenous Peoples, but the concept is new from the Western view. The land is what makes us Indigenous; our creation stories tell us that we evolved from the land. Every day, we acknowledge our ancestral lands and what it means to us: we have a direct relationship with the natural world. We call the earth our mother and the sun our father. This relationship is in our stories, prayers, and songs.

Our Holy people have named these sacred places for what they are and what they represent. Special places that are sacred to us have special meanings. Today, the names of places tell us how different our worldviews are. In the Western worldview, mountains and places are named after humans who were really here last. In the Indigenous worldview, humans acquire their names from their association with the land, mountains, rivers or bodies of water, rain, clouds, minerals, plants, and animals, who were all here before humans. Think about it: what are my clans, and where do you think they came from? Before English names, our elders and ancestors got their names from the natural world.

For Navajo/Diné, we have four sacred mountains that distinguish our ancestral homelands, plus two more mountains: one represents our doorway and the other represents our chimney. To the east is Sisnaajiní, Mount Blanca, near Alamosa, Colorado. To the south is Tsoodził, Mount Taylor in Grants, New Mexico. To the west is Dook’o’ooslííd, the San Francisco Peaks in Flagstaff, Arizona. And to the north is Dibé Nitsaa, Hesperus Mountain in Durango, Colorado. They not only represent the boundaries of our ancestral homelands, but they also watch over us and we consider them as one of nature’s highest council—they are the true leaders and will never steer us wrong.

How Dook’o’ooslííd got its name

The way I was told by my elders, it was way back in time, when the Holy people were designing the land for us to emerge into, this current world. These mountains were intentionally placed in their sacred spaces for our benefit. When Dook’o’ooslííd was placed where it is, there was a cloud formation, a mist, at its tip, and it stayed there for several days. Finally, on the fourth day, the cloud subsided, and when the sun came up and shined its sunlight on the snowy tip of the mountain, the snow reflected the sunlight and created a beautiful rainbow-like pattern, like an abalone shell. The power and energy of the abalone secures the mountain to Mother Earth, and together, they represent the yellow evening sunsets. It’s the same with the other mountains: white shell secures the east mountain, and together they represent the early morning dawn; turquoise secures the south mountain, and together they represent the blue twilight of the day; obsidian secures the northern mountain, and they represent the dark part of the day (nighttime). As you know, to teach and learn, you must provide boundaries and structure for your children. This is how the Holy people thought of us in creating a home for us.

Everything ties to the land

In many ways, our lifeways come from the land. Therefore, the land identifies us as Indigenous Peoples. The land is everything to us. We evolved from the land; it’s where our stories originate. It’s our library, our pharmacy, where our food and all sources that sustain us come from. Our natural laws come from the land, and it’s where our ancestors are buried. Therefore, it’s very important for us to have a land acknowledgement.

My grandmother was very traditional; she didn’t own a watch or live by a calendar. She knew what part of the season it was based on where the sun rose and what time it was based on where the sunlight came in from the ceiling of her hogan as it passed over. She knew what part of the month it was based on the phases of the moon and based on the constellations that appeared in the night sky; she knew when her sheep were having lambs, when to plant and not to plant, when to hunt, and when to tell winter stories and have winter ceremonies. She had a direct relationship with the natural world and the cosmos.

Understanding and moving forward

In order for us to have a relationship and to respect each other, we must know about each other’s background and understand it without judgment. The university is a beacon for this because this is a space that not only supports independent and critical thinking, it also supports diversity, equity, and inclusion. Therefore, it allows for a safe space to share our rich history, culture, and contributions. Whereas our stories were erased in history books.

While in graduate school at NAU, I studied federal Indian policy and laws. I was amazed to learn that our federal government forcefully removed our grandfathers and grandmothers from their ancestral homelands. We weren’t meant to be here today in this day and age. And as if it wasn’t enough to separate us from our homelands, the federal government instituted the boarding school system with the intent to assimilate us by forcefully removing children from their families and culture, cutting off their hair, prohibiting them from speaking their language, and forcing them into Christianity. Would you ever even think about beating your dog so that it becomes a cat?

We are a wealthy nation, but we live in denial. The wealth of our nation could not have been built without stolen lands and free labor, and this has to be acknowledged. But to get to this point, we need to educate ourselves. Universities allow us to express our thoughts. It’s a great place for us to be open-minded, to have meaningful dialogue, be respectful, and establish meaningful relationships, especially during a time of great divisions and polarization. The more you talk about the hard stuff, the easier it becomes. And there’s healing that comes from it—not only for the victim but for the perpetrator. I don’t think we’re asking for an apology from everyone because you and I were not here when these terrible things happened among our ancestors. We’re mainly asking for an acknowledgement of the truth and there’s no harm in that. This is not just an Indigenous problem, so instead of saying, “Get over it!,” everybody needs to be involved and learn about our true history and the trauma that stems from it. This trauma continues to be the root cause of health disparities, social ills, inequity, stereotypes, and systemic racism.

A land acknowledgement helps us open lines of communication and understanding of one another. NAU has a longstanding commitment to serve Native Americans and Indigenous Peoples.

Beyond the land acknowledgement

Today, Indigenous Peoples have representation at NAU—not only among students, but also staff and faculty, and we’re growing. We are given the opportunity to help develop new programs, Indigenizing academia and curricula using our Indigenous worldview. We have a lot to offer through our rich history, culture, and ways of knowing. We are helping to advance NAU’s mission to become the nation’s leading university serving Native Americans and Indigenous Peoples.

NAU’s Native American Cultural Center is unique and the only space of its kind in the Southwest. It’s a living, breathing home away from home. When the center first opened, a medicine person dedicated the building in the same way that Diné people dedicate their hogans or new homes with a blessing of the eastern doorway and the walls that represent the four sacred directions with corn pollen. In this way, the Center represents the beauty and harmony that comes from our ancestral lands and the security of our sacred mountain, Dook’o’ooslííd, the San Francisco Peaks. The center is open to anyone who wants to use it to learn, grow, and build meaningful and lasting relationships.

Together, let’s use NAU’s land acknowledgement to move our conversations forward and elevate our university to new heights.

Ahxéhé (Thank you).