The innovative NAU Elder Cultural Advisors program has been an essential component of NAU’s mission to serve and support Indigenous students. The program, established more than 25 years ago, provides students with cultural and spiritual support from Native American Elders. Elders work one-on-one with students, helping them maintain cultural continuity and balance Native cultural traditions with university life by providing traditional knowledge and teachings on campus. The Elders do not hold faculty positions and are funded through private gifts and grants.

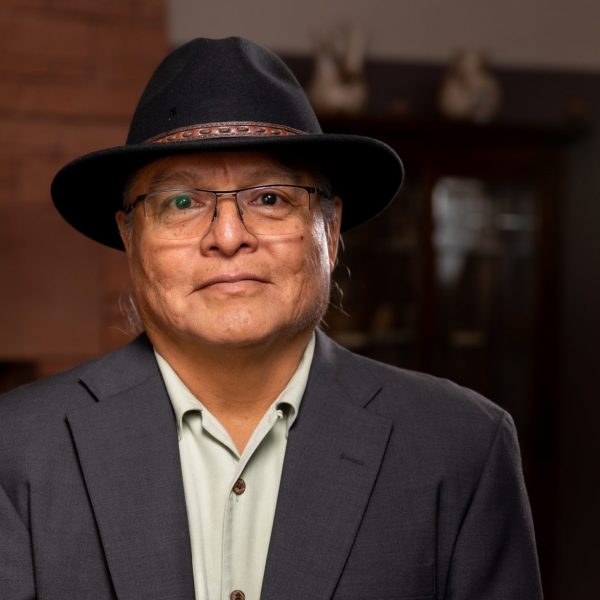

Elder LeRoy Shingoitewa, Hopi, talks about his experiences in this Q&A. You can also read about the other two Elders, Viki Blackgoat, Diné, and Paul Long, Diné.

What is your tribal affiliation and clan information if you care to include it?

Hopi Tribe member, Bear Clan.

Tell us a little about your background—where and how you grew up.

I was born in Keams Canyon, Arizona. My dad worked for BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs), and my mom was the postmistress. When we lived there, I went to the public school. I graduated from NAU in 1969 with a bachelor’s degree in Police Science and Sociology, and my dream was to go into law enforcement. I came home and two jobs were available: police department and a Head Start program teacher. And Head Start paid $1,000 more. I had a family and needed something to live on. That’s how I got into education.

I grew up in a lot of ways traditionally, living on Hopi, and learned a lot of things from my dad, my grandparents, and from my uncles. In Hopi we have extended family, so everybody, in one way or another, will have an influence on your life. I grew up traditionally, very close to the Hopi way, and I learned the Hopi language. Culturally, for me, right now, I can go to both sides, the world of Hopi, and, as we say, the white man’s world.

In 1972, I went back east to Penn State University. I got a chance to get a full-ride scholarship and received a master’s in education leadership. I went back to work on my doctoral degree. I’m an ABD, all-but-dissertation. In those days, it was pretty expensive to go back and defend. I got my dissertation done, but I just never got back to defend it. But I’ve got 27 years in education, two-to-three years as a teacher and then 25 years in management, both outside and in Tribal management. I worked with other Tribes, with the Ute Mountain Ute and the Northern Ute Tribe in Utah, and the Navajo Nation, as an executive assistant in their division of health. That gives you a little bit of my background, both education and where I grew up.

What would you like the campus and community to know about your story?

What I would like the people to see is that our Native students, when given the opportunity to learn, will take advantage of it. For me, fortunately, things happened in my life, the opportunity came. I really want our students to learn that there are times when you have to take a risk; if an opportunity comes, go ahead and take that risk, take a chance and see where it leads you. In 1972, a professor from Penn State was here in Hopi at Polacca Day school. He walked up to me and says, “What’s your name?” I told him what my name was, and he said, “I’m looking for you.” He says, “How would you like to come to Penn State?” I was just like, “Oh yeah, sure,” because I just figured he was kidding. He says, “Okay, I’ll give you a call.” Two weeks later, I received the call. He says, “You’ve been accepted. We’re going to give you a full ride.” So July first of 1972, I ended up heading to Pennsylvania in a Volkswagen, not knowing where I was going, but I was going to go to school. That’s what I would like the community to understand: when opportunity comes, take a chance and see where it leads you. I want them to understand that no matter where they grew up, if you get a chance, take it and see what happens. If I hadn’t taken those chances, I wouldn’t be who I am.

I want the community and our Native people to understand that when they have identity, they have a home. It’s back here where our roots are, and where our Native traditional background is. It doesn’t matter how much traditional knowledge you have, but the fact is, at least you know where you’re from.

What would you like the campus and community to know about your culture?

I would like the community and campus to know that identity is really important to us Native people. And whether you’re a full-blooded Native, like a full-blooded Hopi, or a half-blood or a quarter-blood, you’ve got Native blood in your body, and any way possible, learn about your background. In the long run, that Native identity is going to be what you’re going to depend on as you grow older. I want the community and our Native people to understand that when they have identity, they have a home. It’s back here where our roots are, and where our Native traditional background is. It doesn’t matter how much traditional knowledge you have, but the fact is, at least you know where you’re from. I see this sometimes with those that have grown up off the reservation or are partial blood and share several Tribes, they’re not quite sure where they come from. I really want them to understand that it doesn’t matter which Tribe you belong to. You’re a Tribe person, you have some Native blood in you. Be proud of who you are.

What do the Native American Initiatives’ values of Relationships, Respect, Responsibility, and Resilience mean to you?

That’s being Hopi. That’s the value that I have. For example, respect: my role is to respect everyone that I come in contact with. When I was growing up, my folks told me, “You are always respectful of the Elders. Always give them honor, no matter who they are, and take time to talk to them, take time and ask them questions, because they’re the knowledge of your people.”

Then responsibility: among my people, we have an extended family. Let’s say I belong to, call it the religious side of Hopi. With that and my clanship, I have certain responsibilities. I’ve been told that that’s my responsibility to carry out, so responsibility becomes a serious, real goal that we have as individuals. When we’re given that assignment, you take it seriously. You don’t just do it half-heartedly. You’ve been told this is the role you have to take.

Right now, my role is a grandfather, an uncle, an Elder. I take that role seriously because I figure that through eighty years, I’ve gained some knowledge that might help someone else. And that’s why when I give a presentation to the students at NAU, I go back to what the reservation looked like when I was a kid. No paved roads. We had to deal with cutting wood. We dealt with having to go to the field to work. All these things are part of our life. By giving up the background of where we came from, hopefully, I can give them a picture of what we did during our time, and how, as the word resilience comes up, how we survived. Because among my Hopi people, there is a story as to why we live the way we do. And in that story, it’s been told that as long as we live Hopi, we’re going to be able to be successful in living on this earth. But don’t get lazy. Don’t expect somebody to do the work for you. If you want something done, do it yourself.

The four values that NAU set up really are Native values because that’s how our lives are set up for us to live by. First and foremost are our relationships. Among our people, we don’t just have nuclear family: mother, father, brothers, and sisters. We have an extended family; you’ve got your family that’s associated with your brothers and sisters; then you have clan family, brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers. On top of that, with me, my dad is Sun Clan, and I follow my mom’s side which is a Bear Clan. Well, all the clanship from my dad’s side become my aunts and uncles and that’s some more of the extended family. And then from the godfather to the godmother, another additional clanship shows up and they become a member of my family. What happens then is when things happen ceremonially, and socially, then my role is to support whatever takes place in those families. Why? Because I’m part of their family now, and vice versa.

What do you hope to achieve as a Native American Cultural Center (NACC) Elder?

When I was asked to join the Elders program, that to me was a great honor. First and foremost, being an NAU graduate, I thought, “Wow, I can give back to the university I was at.” And I feel that my role as an NAU Elder is to share my knowledge that I have of life, some of the obstacles I ran into, some of the things to be aware of, and maybe I can have an impact on students. As a principal, I go back to my career, and I keep track of the students that I’ve had under my wing, or I run into them in Flagstaff from the Kinsey school. They’re adults with families now. And out here, the students I had on the reservation, they’re all grown up with families. But I keep track of them. As I see them accomplish something, I’ll write them a little note, say, “Hey, you did it, congratulations.” My role is to be supportive of all the students that we come in contact with or anything that NAU would like me to do, and if I can have some type of influence on a person’s life, then I’m going to be very happy with that. Because maybe down the road, that person may come back, say, “Oh, by the way, I’ve got my doctorate now,” or, “I’ve got this, I’m now working at this.” And then I’ll turn around, say, “Hey, man, you did it. Congratulations, I knew you could.”

What challenges are facing Indigenous students?

The challenge is trying to balance between Native life and outside life, especially if you grew up on, and have never really been off of, the reservation. It’s a huge challenge because they’re going into a whole different world, where the competition is sometimes very fierce, especially when they get into school or into working jobs. Sometimes competition can be demoralizing for people, especially if they don’t have the confidence. The other side is that with the advancement of our computers, the digital age, all this also has today’s students thinking very differently from what we thought when we were kids. In the olden days, you know, we’d sit around the table, and we’d talk as a family. And I don’t see too much of that happening in a modern-day family. You know, if anything I miss right now, is my folks because that’s who I spent time with. Even when they got older, I would just go down to the house and visit and sit and talk.

Something that there needs to be, we call them talking circles. There should be time for talking circles just to throw out some feelings, and there should be no judgment on whatever they throw out because it’s real to the person who’s throwing that issue out. Maybe somebody in that talking circle has somehow also run the same thing but also has an answer on how they were able to face the problem. I think that at NAU if there can be more movement toward that, I think that would really help us.

Why is the NAU land acknowledgement important for the university?

My simple answer is because this is Indian Country. For me, for Hopis, we will tell you that the San Francisco Peak region and this whole area really is Hopi lands. If you go back to the Hopi history, we are the only Tribe in the United States who have never moved from this part of the country. We never were placed anywhere else. We were sent here by our Maker. The lands we sit on we were allowed to use by our maker. On Hopi, we don’t own private lands. We can use the land and we need to take care of it. But in the end, it belongs to the Maker. This acknowledgement verifies that Native people have been here in this country, in this area.

You look at our history of the United States, Native people were here before anyone else ever came to this country. But you also look at the history and say, you know, how come Natives didn’t fight who came here? Well, in the beginning, we welcomed the pilgrims in open arms because that’s what we were told to do. You go to the history of the Pilgrims, and the Pilgrims could have died if it wasn’t for the Native people to feed them, show them how to plant corn, and whatever. At least here in Arizona, that acknowledgement showed up finally. It took a lot of time, but it finally got here and at all three universities. I am so proud of them because they finally put it into writing and officially recognize it that way.

Please provide ways you are inspiring cultural stewardship.

For me, I try to impart some of the teachings that I grew up with about culture, about our beliefs, about the way we do things. Among my Hopi people, there are certain things that some people say are secret but it’s not secret, it’s sacred. And through warnings, we’re told not to expose those things to those who are not Hopi. I choose to decide what is appropriate to tell other Native students, and only within their Native culture or in their Tribes, can they understand what I’m trying to tell them.

One of those things that was taught was to always respect the Elders. Same with children, you know, we bring children in a world and we’re supposed to take care of them. Honor thy mother and father; it’s the same way with that. Listen to them. Thank them. You don’t argue with them. You don’t say things back to them. Sometimes in the outside world, the concept of respect is not there. And it’s sad to see that right now. I try to impart what I grew up traditionally with and what my instructions were. Among Hopis we say if you don’t live being Hopi, that the day’s going to come that you’re going to be judged by how you live. And, of course, I know my mom and my dad always said that you treat everybody good. Say hello to them. Take a few minutes talk to them. That’s what I want young people to do.

I also want young people to feel comfortable in talking with an Elder. If you want to hear something, come ask me. I’ll tell you what I know. When you meet an Elder, they’re ready to tell you whatever. They’re willing to tell stories to you about their life. I think that what I want to impart to our young people is that life involves all people, not just their own age group. There’s a lot of good people out there.

Can you share a specific moment when interacting with an NAU student as an Elder that you find memorable?

Since I’ve been in the program, I am usually there [at the Native American Cultural Center] early. And so I’ll sit out on the couch that’s there in the foyer. And a student will just come up and say, “Hey, I’ve got something to ask you.” And they’ll ask me the question and of course, I’ll impart what I’m going to. Then, pretty soon, other students start to come around, they start to sit down because they feel comfortable enough to come and sit and listen. They’re sitting there listening to what we’re talking about, so for me, what’s memorable is being able to gather young people around me. In the Hopi way, it’s like me being a storyteller, you know, telling the stories of my experience, and maybe that’s something they’re going to remember as they go through their academic life.

Being a university student is not an easy job. You got to deal with finances. You got to deal with homework. You got to deal with papers. You got to deal with parents at home who say, “Hey, you got to come home for a ceremony this weekend,” and you’re sitting there going, “Hey, but I’ve got a test that I’ve got to be here for.” It becomes a tough road to run.

Like I said, for me, memorable moments are working with young people. I’ve done it all my life. For me, it’s a joy just to work with young people. Actually, I just enjoy working with people, no matter who they are.

What is your family history with NAU?

My youngest sister went to school there and got her degree. My granddaughter, who is now one of the event directors at the Museum of Northern Arizona, she got her Library Science degree there. I’ve got a niece going there right now. Really, NAU has been the leader of Native American education since its inception.

What is your favorite part of being a NACC Elder?

It’s keeping me young! That’s really true. You know, when you get an age as I am, you think about what I can do to keep myself active and keep my mind fresh. Going to NAU has educated me, because now I’m in relationship with young people who have sometimes a little different mindset about what they’re trying to achieve. But in the long run, they’re all looking for, “Who do I belong to? Where do I belong? Maybe I can get some help here.”

A lot of our young people, one of the areas they really feel left out of is the language. And I think that because they didn’t learn their language, they assume or people assume that they don’t belong to a Tribe. I try to tell young people that it’s never too late to start learning the language. I think sometimes we, as Native Elders, or those who live out here on the reservation, we don’t take the time to work with them, but we’ll laugh at them because they don’t say a word right. For me, I try to teach the words so that, at least conversationally, they can understand it, and work with repeating themselves. Every chance I get when I talk, especially to a Hopi person, I’ll talk Hopi to them. I’m going to talk to you in Hopi and you can ask me what I said. And I’ll interpret it and eventually, you’re going to catch on.

With me, my favorite part of being an NAU Elder is that, throughout the semester, I get to come in and meet with young people. And a lot of our Elders here on Hopi don’t get that chance and I get it. Me, I feel blessed to do that.

Plus, I think also that the staff at the Native American Cultural Center are really full of energy. I’m glad to see NAU is also pulling Native people into positions; I’m seeing more Native professionals coming into NAU. I like that. I like that because it shows that Native people are at an even level with any other culture that exists on the NAU campus.

Is there anything else that you would like to share?

One of the things that I’d want the Native community to share is that the Native American students and NAU are part of the city of Flagstaff. I want the community to understand that we, as Native people, are contributors to Flagstaff. You know, for Hopi, we own three properties there in Flagstaff. We own the Continental shopping center, we own Kachina Plaza, and we own downtown Heritage Square. And some people don’t know that. If you go to the Museum of Northern Arizona, my dad was one of the original workers who worked with Miss Colton. (Editor’s note: Mary-Russell Farrell Colton was one of the principal founders of the museum.) My ties to Flagstaff go a long way back. That’s what I want the community to understand, that we, as Native people—students and the people who live in Flagstaff—we are contributing members to Flagstaff, Arizona.