Assistant professor couple work to discover novel ways to assist American Indian and Alaska Native people through their cancer research

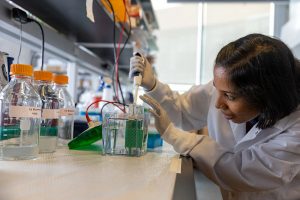

In their Cancer Biochemistry and Immunology Labs dedicated to cancer research, Archana Varadaraj and Narendiran Rajasekaran are discovering and developing new, innovative therapies to cure treatment-resistant cancers, especially breast, renal and colorectal cancers.

The Northern Arizona University chemistry and biochemistry power couple, both assistant professors, have dedicated their cancer research projects with the Southwest Health Equity Research Collaborative (SHERC) to discovering real-world cancer solutions with a special focus on assisting people who are underrepresented.

“With cancer biochemistry and immunology being new research fields at NAU, we needed to first build the infrastructure and expertise from scratch to initiate research,” Varadaraj said. “This was challenging and fulfilling considering we were both early-stage investigators. Through our grants from SHERC, we were able to establish our labs with state-of-the-art infrastructure in our respective fields.”

Rajasekaran chose his SHERC research project after discovering that colorectal cancer and breast cancer survival rates are worse for American Indian and Alaska Native people since they are more likely to be diagnosed with diseases at a later stage leading to poor treatment outcomes and increased mortality. These disparities in cancer survival rates in the American Indian and Alaska Native populations are compounded by resistance to existing therapies and high relapse rates among patients.

“Cancer immunotherapy has shown promising results in patients refractory to standard chemotherapy and with a high risk of disease recurrence,” Rajasekaran said. “Factors within the tumor microenvironment influence the sensitivity to immunotherapy and a better understanding of the immune responses within the tumor microenvironment is important to provide new approaches in improving the efficiency of current immunotherapies.”

Varadaraj also found similar results with underrepresented populations and breast cancer.

“Breast and renal cancers disproportionately affect minority communities,” Varadaraj said. “A rigorous understanding of the disease informs better treatment options and personalized health care in racially disparate populations.”

Studying tissue building to prevent breast cancer

Varadaraj created the Varadaraj Lab at NAU to pursue her interest in understanding the tumor microenvironment of cancer, which includes blood vessels, immune and other cells, and extracellular matrix proteins. Her work specifically focuses on how the extracellular matrix proteins, which are used by the body for tissue building––including collagen, fibrin, fibronectin, gelatin and other material––affect diseases such as cancer through the tumor microenvironment.

Varadaraj created the Varadaraj Lab at NAU to pursue her interest in understanding the tumor microenvironment of cancer, which includes blood vessels, immune and other cells, and extracellular matrix proteins. Her work specifically focuses on how the extracellular matrix proteins, which are used by the body for tissue building––including collagen, fibrin, fibronectin, gelatin and other material––affect diseases such as cancer through the tumor microenvironment.

“In previous work, we discovered that the matrix protein fibronectin is continuously turned over by specific cancer-promoting cytokines [secretions that cells release to communicate and interact with other cells], causing cells to alter how fibronectin is assembled,” Varadaraj said.

She said that in the same study, her team showed that breast cells that modify how it constructs fibronectin critically influence how these normal cells switch to becoming cancer cells.

In their SHERC-funded project, “Fibrillogenesis Mediated Phenotype Switching of Breast Cancer Cells,” the team addressed whether a disposition toward cancer may be driven simply by altering the assembly states of fibronectin in the absence of well-established cancer promoters.

“Although cancers have a well-defined genetic basis, we wanted to know if altering the microenvironment of the cancer was sufficient to arrive at a tumorigenic/cancer state,” she said.

Their work, which resulted in the publication, “Fibronectin Assembly Regulates Lumen Formation in Breast Acini,” proved that factors or events that change the construction state of fibronectin in breast cells are enough to create cancer.

“We showed for the first time that it was possible to switch normal breast cells into their cancer counterparts by preventing the assembly of fibronectin using specific inhibitory peptides in normal cells,” she said.

The team has extended some of these findings to renal cancers, specifically to understand drug resistance and to identify specific mechanisms that cause this resistant phenotype.

“We have also extended our findings to diseases such as fibrosis, commonly associated with cancers,” Varadaraj said. “This work is currently funded by the National Institutes of Health.”

Decoding the role of natural killer cells

The Rajasekaran Lab works on unraveling the role of natural killer (NK) cells, a superpower in anti-tumor immune responses, to create new forms of cancer therapies.

The Rajasekaran Lab works on unraveling the role of natural killer (NK) cells, a superpower in anti-tumor immune responses, to create new forms of cancer therapies.

Rajasekaran and his team also examine the effect of oncolytic viruses on NK cell performance. Oncolytic reoviruses are a form of immunotherapy that target and kill tumor cells, but their effect on NK cells is still unknown.

“Our study establishes NK cells as strong therapeutic candidates to treat solid tumors,” Rajasekaran said.

His SHERC research project, “Investigating the Anti-tumor Cytotoxicity of Reovirus-Treated NK Cells for Cancer Therapy,” examines approaches to enhance the body’s defenses against cancer.

Results from the study were published earlier this year in the Journal of Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy titled “Hypoxia-inducible Factor-1 Alpha Expression is Induced by IL-2 via the PI3K/mTOR Pathway in Hypoxic NK Cells and Supports Effector Functions in NKL Cells and Ex Vivo Expanded NK Cells.”

“The studies have opened new avenues for the treatment of solid tumors like triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) that disproportionately affect American Indian, Alaska Native and Hispanic populations,” he said.

Rajasekaran said that future grants will focus on understanding how NK cells can be manipulated to efficiently kill tumors in hypoxic tumor microenvironments in TNBC and RCC patients.

“Data from such a study will help us devise novel NK cell-based therapeutic strategies to treat these cancers in AI/AN and Hispanic populations,” Rajasekaran said.

This research was supported by an NIMHD center grant to the Southwest Health Equity Research Collaborative at Northern Arizona University (U54MD012388).