In the spring of 2020, SCA received a call from Mike Dehoff who modestly called himself a member of a “group of non-academic people following a curiosity.” As a river runner and Moab business owner, Mike was in the process of forming a group that aspired to partner with non-profits to investigate rapids that were re- emerging in the Colorado River due to the mega drought. Mike had discovered some Kolb film reels in our digital collections that might be useful for comparing with rapids that were beginning to re-emerge. Since that first contact in 2020, Mike’s endeavor has grown from a passion project into the formal Returning Rapids Project. He was generous enough to take the time to answer some questions we had about this incredible work and how it all came together.

How did the Returning Rapids Project get started?

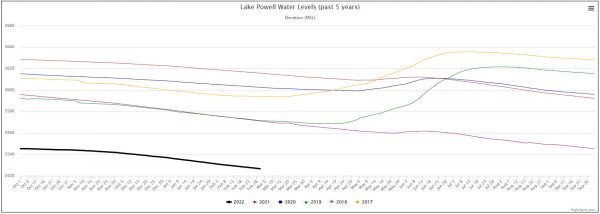

In the early part of the 2000s there was a very, very dry year – even by today’s standards. The winter of 2001/2002 produced a snowpack that was roughly 30-35% of normal. For many people who were running the Colorado River through Cataract Canyon, it was hard not to notice the drastic change as the reservoir known as lake Powell receded. Over the next 4 years it dropped 150 feet.

Cataract Canyon river maps published during the 1990s had zones marked as “Areas Inundated by Lake Powell.” When the reservoir started to drop, it was easy to get curious and wonder what was there before the reservoir flooded the lower half of Cataract Canyon.

Over the latter part of the 2000s and into the early 2010s, rapids started re-appearing along the river in areas that used to be still water, in the reservoir zone. These rapids were being carved out of the giant layer of mud, of river sediment that the reservoir caused to be dropped out in Cataract Canyon – burying the rapids and river corridor.

During this time, there was a lot of conversation among my friends about what was happening in lower Cataract Canyon, including my good friend Steve “T-Berry” Young, who was the head river ranger for Canyonlands at the time. We would wonder why there wasn’t a specific effort to study the changes in this area. Especially since the river corridor was slowly revealing more and more as the mud was carved away.

In the mid-2010s, I went to a river running event at the John Wesley Powell Museum in Green River, Utah. There was a geologist giving a talk about Colorado Plateau geology. At the end of his talk, he invited questions. I raised my hand and asked something like, “We are seeing rapids get carved out of the mud in lower Cataract Canyon that haven’t been seen since they were flooded. Do you know how many rapids there were and how many we can expect to see again?”

The geologist said one or two sentences about the lower part of the Grand Canyon and how it is dealing with the inundation of Lake Mead, then went back to discussing the various layers in Grand Canyon. I remember thinking “Huh, you didn’t even try to answer my question.”

About this time, my girlfriend Meg Flynn, got a job at the local Grand County Public Library here in Moab, Utah. On a trip through Cataract, she and I talked a lot about what materials might be available to help discover how many rapids were in Cataract Canyon. That trip was in 2013. We were camped at Clearwater Canyon (photo attached) – a very special place that has been drastically impacted by lake Powell. (and as an editorial note – its not a real Lake so it doesn’t get a capital L.)

After that trip, Meg helped me find an old guidebook – the 1971 Powell Society Guide “River Runners Guide to The Canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers.” It was published while the reservoir was filling and had a great amount of detail regarding how many rapids were in Cataract Canyon and where they were located.

It wasn’t long after that, I created a spreadsheet to track where the rapids were – and more importantly what elevations I thought they were at. The level of lake Powell is measured in elevation. The more the elevation dropped, the more it exposed the sediment beds, which allowed the river to carve away mud and expose old rapids.

This spreadsheet grew to the point that I started sharing it with the folks at the Canyonlands National Park Reservation office.They were the ones issuing permits for Cataract Canyon and were trying to advise visitors what to expect regarding the changing reservoir levels.

Then 3 key things happened, Meg and I got married and she started a program to get her Master’s degree in Library Science. I switched my side hustle as a river equipment Welder/Fabricator to a full-time job and opened up the Eddyline Welding shop in Moab. And I met Peter Lefebrve.

Peter has been a long-time river guide, running rivers all around the Colorado Plateau. He would come by my shop and we would chat about river running. We soon discovered that we shared an interest in watching the changes in lower Cataract Canyon. He regularly took pictures at the mouths of the side canyons to try to document the changes he was observing.

As Meg worked her way through her Master’s program, she gained a much better understanding of how to navigate archives and special collections to pursue research questions. It was through her growing knowledge that I learned about really great collections of photos, maps, and other written materials that were housed in various places – like the Cline Library’s Special Collections.

Peter would come by the shop between his river trips and we would compare notes about the changes we were seeing in Cataract. At home, during times when Meg was diligently completing her MLS program work, I would search through the various archives that housed photos of Cataract Canyon.

During this time there were a few other key people who also helped spring the project forward. Bego Gerhart helped with early efforts. John Weisheit with Living Rivers shared a private collection of George Simmons maps and photos, and Robert Tubbs shared his Cataract scroll map made by Les Jones in 1963. The map was a great resource for finding where rapids were and their historic elevations.

This takes us up to 2017-2018. In these years we were compiling a lot of historic photos. They were housed in a binder which we began loaning to people to take on river trips.

Peter had been watching some rocks that were just upstream of a large side canyon called Gypsum Canyon. Gypsum Canyon had a rapid at its mouth that was reputed to be a fierce one prior to the reservoir. We became keenly interested in Gypsum Canyon Rapid as we thought it might be close to returning.

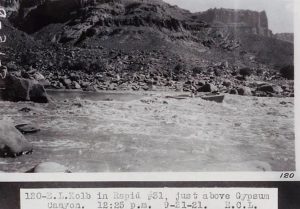

It was during this time that a key photo from the Cline Library Kolb Brothers collection came into play. The rocks that Peter had been watching just upstream of Gypsum Canyon matched up perfectly with a randomly taken photo that we had. This was a very big “A-HA” moment. The rocks were still all in the same place, the rapid was returning and had a very similar layout.

During the summer of 2018, I had an odd project in the Eddyline Welding shop that involved outfitting a roto molded plastic drift boat into something liked a decked over dory. The boat was to be used on a Green River source to sea trip by a staff member from the American Rivers organization. This person, Mike Fiebig, was taking a sabbatical from his position working to protect rivers in Montana. Mike and his wife Jenny were going to use the dory on most of their trip. They asked if Meg and I wanted to join them on the Cataract Canyon stretch of their expedition.

On Mike and Jenny Fiebig’s trip through Cataract, we met a lot of folks. One of them was Seth Arens who works for Western Water Assessment and is housed by the Center for Global Change and Sustainability at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. After showing everyone our material on the Fiebig trip, Seth Arens proposed that we convene a broad coalition of university staff and potentially students to look at the changes we were trying to document.

In 2019, the project really started to take off. We published our first “Field Binder” which was an 80-page pamphlet that helped people running through Cataract Canyon understand what was and is happening. That fall the first science trip was put together by Seth Arens and the Center for Global Change and Sustainability. It was a collaborative trip with many University of Utah Faculty and Utah Water Science Center USGS staffers.

On the first fall science trip, we had another A-Ha moment. Not so much for Peter and I, but we were able to watch all these highly educated experts in their fields wrap their minds around what we were seeing. It was also on this trip that we met another key player in the Returning Rapids partnership – Scott Hynek from the Utah Water Science Center.

The connection with Scott was important in a few ways. First, Scott brought an unassuming attitude with him. It is important to understand that up to this point Peter and myself had endured a lot of “Who are you guys with again?” “You’re are trying to do what?” and “What agency are you with?” … None of that came from Scott (and may other parties on the first science trip). But Scott and his research team had also been working on many lake Powell related tasks – the main one being the growing sediment delta. They were charged with answering the question: “If the reservoir is 30-ish % full, how much of that is sediment?”

It was on the 2019 trip that another key thing changed while talking with one of the USGS scientists. Prior to the trip, people just called the banks of sediment along the river the “lake Powell Formation” or just “the mud.” David O’Leary of the USGS raised a protest to the terminology by saying – “John Wesley Powell’s name has been insulted enough by this reservoir being named after him – this mud shouldn’t be named after him also.” And in that moment, someone on the trip said, “Then maybe it should be called the ‘Dominy’ Formation” (Floyd Dominy was the head of the Bureau of Reclamation and championed the building of Glen Canyon Dam) and that name stuck.

It was that winter that I arranged a meeting with Eric Balken who is the Executive Director of the Glen Canyon Institute (GCI). Meg and I met with Eric and broached the idea of working together – and to be umbrellaed under their 501 c3 non-profit status. Up to that point we had been doing everything out of our own pockets –volunteering our time and spending our own money. Eric and the rest of GCI agreed and we were now able to receive donations to cover our expenses. The Returning Rapids Project is now a project under the Glen Canyon Institute.

Since that first science trip a lot has happened. I will get into that in the following q&a. There is also more material on our website returingrapids.com

What has been the most significant accomplishment of the project thus far?

Three things:

1. Drawing attention to the changes we are seeing in Cataract Canyon. We have had river guides tell us that when they have our field binders with them so their passengers can read them it has “changed their trip.” The way we are communicating what we are seeing is helping people understand and care about a place that many people gave up on once it was drowned under lake Powell.

2. Getting a broad range of scientists to work together on our science trips and overall efforts. It is so great to sit around camp and listen to all the different perspectives, ideas, and discoveries that people share.

3. The “Dominy Formation” name. It has stuck and is well deserved.

What one or two aspects of the project would you like everyone to know about?

Recently, a person who is director level position for a national river advocacy agency said to me, “I finally get it! For so many things “Colorado River” the Grand Canyon sucks all the air out of the room.” That keeps resonating with me. The Grand Canyon is an important and beautiful place but so is Cataract, Glen, and many other places along our beloved river.

If we only focus our attention and stewardship on one place, then it is easy to lever other places out of favor… and make it easier to justify things like a big Dam project.

The consequences from this line of thinking continue to have an impact. A simple example: I spoke with someone who was a National Park Service photographer in the 1990s and 2000s and asked if they had any pictures of the areas where we are now seeing so much change. Their answer, “You know, while I don’t want to admit it, after watching the river turn into the reservoir, I just set my camera down. I didn’t take pictures because it wasn’t a river anymore.”

What I would like everyone to know, and it seems so true in the face of climate change now, is that we all have to pay attention and leave room for/ not give up hope that the world’s natural forces can make big advances towards restoring themselves from the impacts of our cultural manifest destiny. We just have to give it a chance. And where we can, we should make it a conscious effort.

The other thing I would like everyone to know, is it sure seems to me that what we have going on regarding our water storage and delivery system isn’t working. If you go back and read the book “Encounters with the Archdruid” on the pages where Floyd Dominy is debating David Brower from the Sierra Club, Dominy admits that in the future we will find better ways to deal with water in the southwest. That was 60 years ago… and it sure seems to me like we need to do some re-thinking.

What role have libraries and archives played in the development of the Returning Rapids Project and the final products of the project?

Libraries and librarians tend to be the unsung heroes of information organization and underpinning of so many research projects.

What would Google be if it wasn’t modeled after an incredibly effective librarian?

I suppose with those two initial statements, I have showed my hand. There is no way we would have the level of understanding of the arc of change in Cataract Canyon without photos that someone took care to identify and archive thanks to valuing the preservation of information so it someone can reference it in the near or distant future.

Having access to the information – photos, maps, narratives contained in archives has served as a trail of breadcrumbs and treasure maps to help unwind our curiosities.

That we have an incredibly skilled librarian as a core member of our team has been an invaluable asset when navigating search results, investigating new threads, and tracking all the metadata. It has been foundational to us finding our way and being able to retrace our steps through the vast amount of information housed online.

Also, as our photo archive grows, Meg has been essential for helping to organize our information.

How did you discover the resources at Cline Library Special Collections and Archives that are supporting your project?

The Cline Library Special Collections contains one of the biggest archives of info about the Colorado River and its history.

Initially, search results just pop up and take you into the Cline’s digitized materials. But the layout of the site allows you to search all the different angles that may yield more info.

We specifically found the Kolb brothers collection very helpful. Their 1911 trip and then the 1921 USGS survey trip that they were a part of did a great job of documenting the areas they traveled through.

We are working on a big re-edit of the Kolb Brothers Film Reels. The reels that they showed in their South Rim of the Grand Canyon studio tend to have a lot of footage from the 1921 USGS survey trip through Cataract Canyon. Using all the other photos in our project archive, we were able to further identify reel shots by location. Currently, we are working on re-editing the reels in an upstream to downstream fashion. It will let us see a run through Cataract Canyon as the Kolbs were able to capture it. This includes footage of many rapids that were buried under the waters of lake Powell.

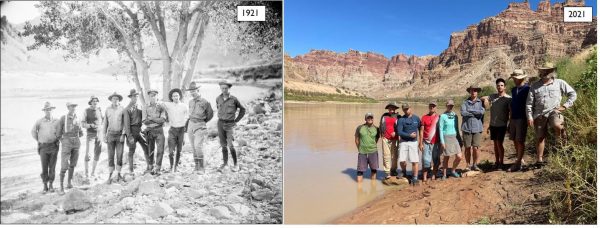

Additionally, in September 2021, we were able to do a 100 years later photo recreation trip with many of the photos from the 1921 USGS trip. Peter and Cindy at Special Collections were very helpful in getting us materials to make this happen. You can see the trip report from this trip: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1sXKEAC8m_Y1lvnm9cUp34HoVufhYFRDe/view

What do you see as the future for the Returning Rapids project?

We like to summarize our project with, “we go boating, take pictures, and tell the story of the changes we are seeing.”

The project is growing through the numbers of people who want to see the results of our research and the story of changes along the river.

Some of the scientists we collaborate with are delving into much deeper levels of research. There have been several attempts to be funded by the National Science Foundation.

In an ideal world, maybe an effort similar to the Grand Canyon Research and Monitoring Center could be formed.

If we can tell a large number of people the story of the changes we are seeing in a simple manner, maybe it can affect our relation with the Colorado River.

What future do you see for the greater Glen Canyon area in the 10-20 years?

I think there is a simple fact we need to face. There isn’t enough water in the Colorado River system to keep 2 large reservoirs full. Also, this method of water storage isn’t the most effective means to store and deliver water to users. And it isn’t a healthy way to maintain some semblance of the ecosystem that the Colorado once was.

When people who understand water law start explaining to me all the different aspects regarding who gets what and why, I come back to a simple thought, “This is one of the most convoluted expressions of greed that there is in modern society.”

So, when you put those 2 things together – not enough water and a convoluted expression of greed, it leaves me feeling very uncertain about a clear future for Glen Canyon. When I am sitting next to the river in a place that is so quickly showing signs of recovery, I can’t help but think that the natural world will force its hand before our governmental dysfunctions can find a good solution.

I think the most practical solution is to put whatever water there is in lake Powell into lake Mead – that would be the lower basin’s storage pool. For the upper basin states, it just doesn’t make sense to have a reservoir right on the tail end of the “upper” basin – its dumb. Why not keep all the high elevation reservoirs as full as possible and just get rid of Powell entirely?

What has been your most unexpected discovery thus far?

There have been unexpected discoveries each year.

We found ancient structures half buried in mud and petroglyph panels that were once under reservoir waters.

Last fall we discovered bedrock strata emerging out of the mud near the North Wash take out – which means that we could see rapid or waterfall similar to the ones at Piute Farms in the San Juan and Pearce Ferry just downstream from the Grand Wash Cliffs.

But the 2 biggest discoveries that I am so surprised about are:

During the planning stage of the Dam and potential reservoir, I am amazed at how little was known about the areas the project was going to effect. When I read through old reports, some are outright apologetic about how they couldn’t survey everything. Additionally, all the survey information was never compiled into one singular document to fully inform the decision and address the true cost of the project.

Right now, the biggest discovery for me is not an easy one. Anyone who knows the Colorado in its true form knows how much mud the river moves. All that mud settles out of the river and into the reservoir. It is what has buried the rapids in Cataract Canyon. As the reservoir level declines, the muddy sediment delta continues to grow and is now moving.

I think of it like this – in the 1960s/1970s Glen and Cataract Canyons were flooded by water. Now we are watching a giant mud glacier that formed in Cataract slowly creep and grow as it moves into Glen Canyon.

I have had a chance to meet several state and federal government officials and ask them “Who is in charge of the mud?” So far, I have not received an answer that gives me any faith that what is now 2.25 cubic kilometers of mud (and growing) will be purposely managed by any government agency.

If so many states in the southwest United States claim a percentage of the Colorado River’s water, they should also take responsibility for their percentage of the byproduct, the mud. There are currently no efforts to do so – it’s just a by-product that is piling up in a place with National Park level characteristics.