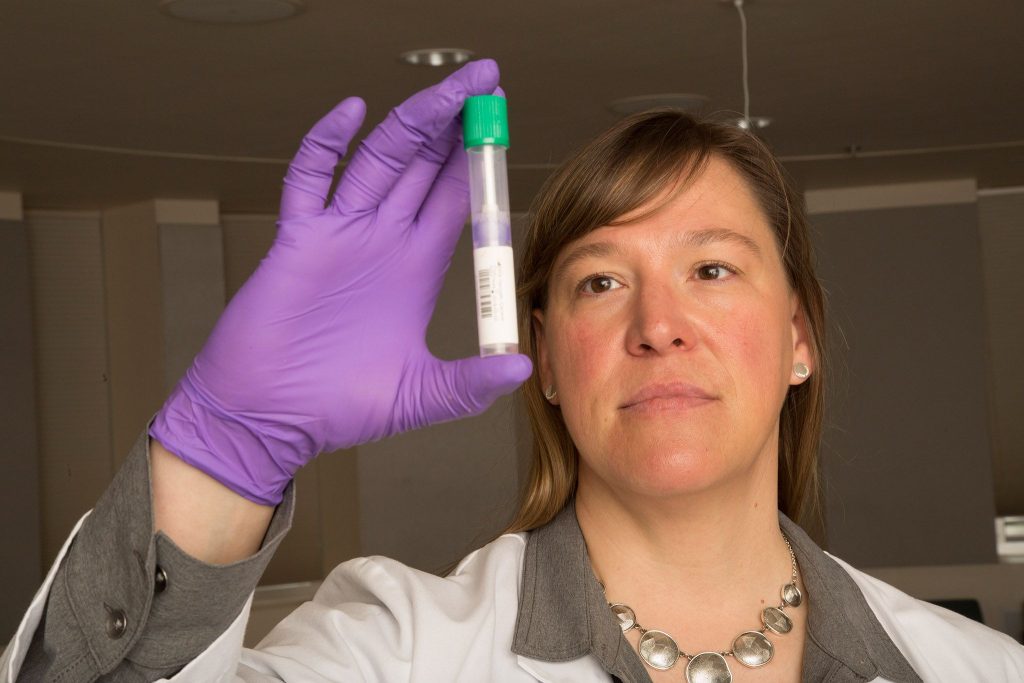

Disease ecologist Bridget Barker investigates Valley Fever, a potentially deadly disease spreading across the Southwest.

To her colleagues, she’s become known as “the Queen of Cocci” because she’s cultivated her specialty studying the pathogens Coccidioides immitis and C. posadasii (cocci for short), which cause the disease Coccidioidomycosis, better known as Valley Fever. Associate Professor Bridget Barker of NAU’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute pioneered much of the basic research in this field, building her career on investigating the ecology and population genetics of cocci, host, and fungal mRNA/protein analysis during early infection, as well as detecting cocci in the soil.

Valley Fever infects thousands of Americans each year

A potentially deadly, dust-borne fungal disease, Valley Fever is one of the most commonly reported infectious diseases in Arizona. Endemic to the desert Southwest, it is spreading throughout the region as well as Mexico and South America. The microscopic fungus lives in desert soils and typically enters the body through the lungs. Valley Fever infects an estimated 150,000 Americans annually, and kills as many as 500 each year.

Although 60 percent of people infected experience no or mild symptoms, 40 percent experience fever, cough, fatigue, chest pain, shortness of breath, and rash. In fewer than five percent of people with symptoms, it can cause severe respiratory disease requiring treatment with antifungal medication. There is no vaccine or cure, and preventing infection is difficult.

Field shifts from clinical practice to research focus

Barker is one of only a few scientists working on basic research in this highly specialized field. Until recently, most of the work being done was led by physicians scrambling to diagnose and treat the disease. Over the last few years, however, there has been a shift toward research. “This has been a great year to reflect on where we are as a field and how much we’ve grown over the last few years. There are only a handful of us doing more basic research. We’re not clinicians or MDs, but we’re coming at this from the perspective of ecology, evolution, and fungal genetics of the organism,” she says.

“When I first became more involved in the Cocci study group, it was really a shift for them to hear a different perspective, but I’m very persistent,” Barker adds. “I just kept showing up to the meetings, presenting our research, and telling them how interesting this pathogen is. As an organism, it has an interesting life cycle. It has an interesting ecology that’s very different, unique from other fungi, beyond the disease-causing piece of it. It has a very diverse genome, so each individual fungus we collect from a patient or from the environment is a unique individual. There are no clones, so there are all these fascinating implications that surface.”

Early on, Barker was involved in characterizing the first genomes for cocci in a study funded through a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). “One of the papers coming out of that study was based on my research exploring all sorts of crazy, cool things about cocci biology, like the organisms are having sex in the environment and they’re exchanging genes and recombining. But no one had ever seen its sexual lifecycle before.”

Projects include major collaborations

Barker is currently focusing on several major projects. As one of the leading Valley Fever researchers in Arizona, Barker recently joined a partnership between NAU, The University of Arizona, and Arizona State University. Funded through a $3.1 million grant from the Arizona Board of Regents, this integrated, statewide project brings together scientists to learn more about the environmental markers of Valley Fever and find a solution to this longstanding problem. Researchers will work together to identify, characterize, and map hotspots and routes of exposure for Valley Fever, boosting detection technology, genomics, and seasonal outbreak patterns. Barker will lead a team pairing air and soil sampling.

Barker is also on another project funded by the NIAID, collaborating with a team of scientists at the University of San Francisco to investigate potential diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines—research that will fill some of the significant knowledge gaps about Valley Fever. The team will use CRISPR/Cas9 technology to develop mutant strains of Coccidioides to test virulence and host response to infection.

“We can engineer CRISPR enzymes to cut out genes that we think are associated with its ability to cause disease. It has this whole other morphology in the host, and we don’t understand which genes are involved other than at a very rudimentary level. So, we’re going to go in and decide which genes we’re going to knock out. We’ll be answering questions like whether they have a phenotype, whether they are less virulent in mice, and whether they grow slower or faster,” she explains.

The moment I realized this was my passion was while traveling to a meeting to present my first results on the work I had done, and I sat next to someone who had been impacted by the disease. That really brought it home that this work would help people, and no one else was doing it!

In addition, she runs a long-term project studying how Valley Fever affects different breeds of dogs. The team recruits dog owners to swab their dogs’ mouths and return the samples back to the lab, where students extract DNA for analysis. So far, they have received about 3,000 responses, leading them to find that certain breeds, including Boxers and Labrador Retrievers, seem to be more susceptible, while one breed might be more resistant—Chihuahuas.

Barker co-invented a patented technology that provides assays, methods, and kits for detecting and quantifying Coccidioides species in samples collected from the soil, air, water, solid surfaces, culture media, and foodstuffs. “It works beautifully,” she says, “and other labs are using it now, including the CDC, and our colleagues at UC Berkeley are using it extensively.”

Finding her true passion

Barker found her true passion studying Valley Fever. “I think the moment I realized this was my passion was while traveling to a meeting to present my first results on the work I had done to detect the organism in the soil, and I sat next to someone who had been impacted by the disease. That really brought it home that this work would help people, and no one else was doing it!”

Studying cocci lets Barker combine her passion for discovery with the fulfillment of protecting her fellow humans. “From a basic research perspective, the organism is fascinating, the ecology is fascinating, and the evolution is fascinating. But there’s also this piece that just inspires me—the part where I could directly make a difference in people’s lives by researching this organism; trying to understand its biology; trying to figure out its Achilles heel—and how we’re going to defeat the organism.”

Read more about Barker’s career path to becoming “the Queen of Cocci.”