Oohs and aahs abound when you see images from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

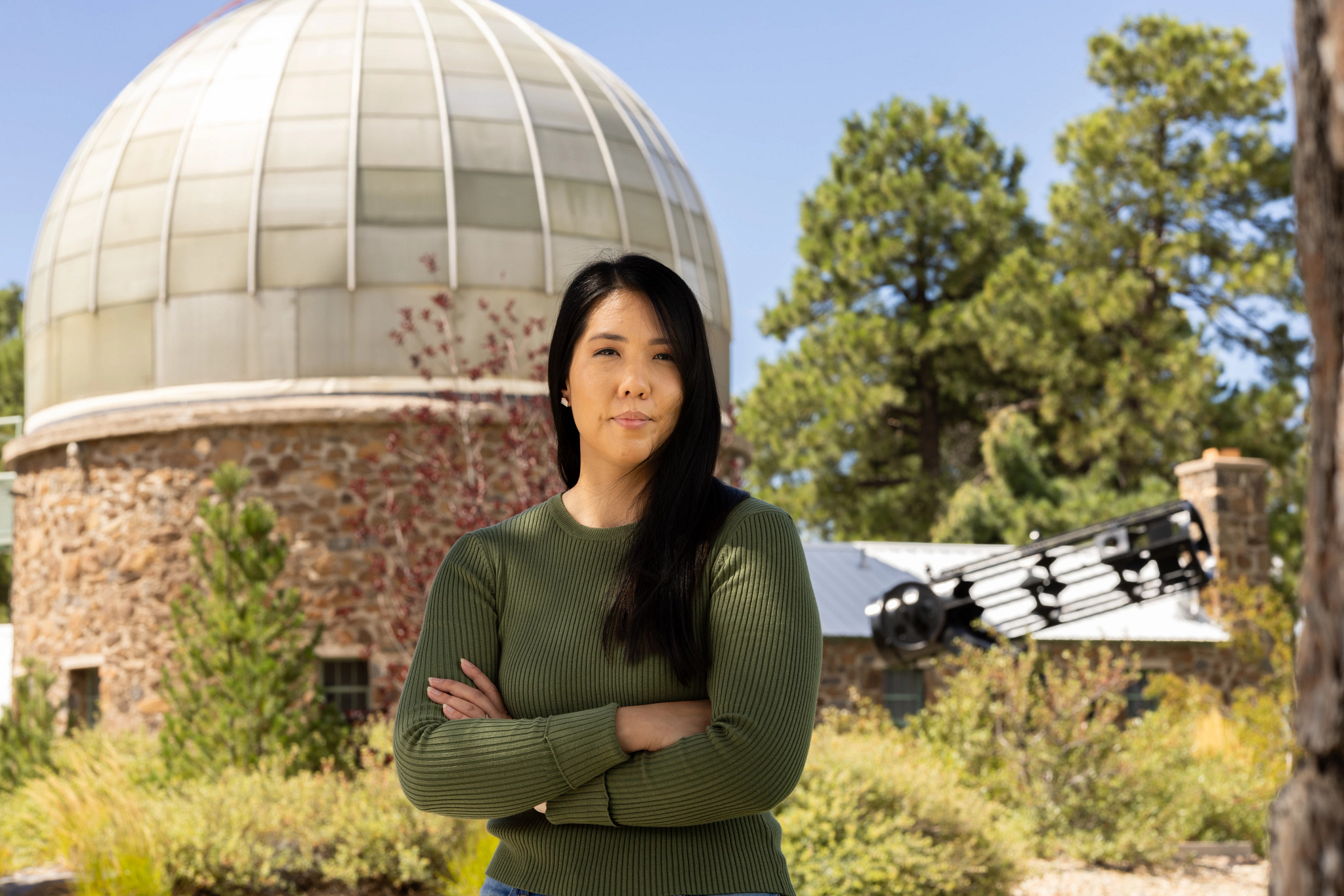

Free of Earth’s atmosphere, these telescopes capture images in vivid detail and see deep into space. For most people, the telescopes offer views they could previously only imagine. For astronomers like Ana Morgan, these telescopes are tools to make measurements that Earth-based telescopes might miss.

Morgan, an NAU PhD student in Astronomy and Planetary Science, is working on two projects with the space telescopes. Both projects study trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). TNOs are minor planets that orbit the sun beyond Neptune.

For one project, Morgan is working with its principal investigator (PI) and her mentor, Professor and Chair David Trilling of the Astronomy and Planetary Science department. The other team members are from the US, Canada, and Chile. They are using both the HST and JWST to study the size and distribution of TNOs. Additionally, Morgan is the lead on a project selected by the HST team to look at archived images of excited TNOs—those outside their typical orbit.

Choosing planetary science at NAU

Morgan grew up in the small Colorado town of Kiowa. As an engineering major at the University of Colorado Boulder, she included an astronomy class in her schedule—that’s all it took. She switched majors and graduated with a degree in astronomy and an astrophysics emphasis. She then had to decide whether to continue studying astrophysics—the birth, life, and death of stars, galaxies, and nebulae—or switch to planetary astronomy—the study of objects in our solar system.

Once she decided on planetary astronomy, NAU was the best fit. “I saw NAU and the faculty,” Morgan says. “The department is very much focused on planetary science and small bodies, which I’m particularly interested in.” She jumped right into the TNO project during the first year of her program.

Studying minor planets with the Hubble Space Telescope

TNOs are icy bodies that orbit in a belt much like the asteroid belt but much, much farther out. As their name indicates, TNOs’ average orbits bring them just beyond Neptune’s at 30 astronomical units (AU) or greater. One AU is 93 million miles, Earth’s distance from the sun. The largest TNOs discovered so far are smaller than Earth’s moon. Dwarf planet Pluto is the most famous TNO.

Astronomers think TNOs are remnants from when the solar system first formed and can offer clues to its beginning. “They are some of the most pristine objects in our solar system. So, there’s a lot of history sitting in those objects,” Morgan says. “Studying them will help us understand the formation and evolution of our solar system.”

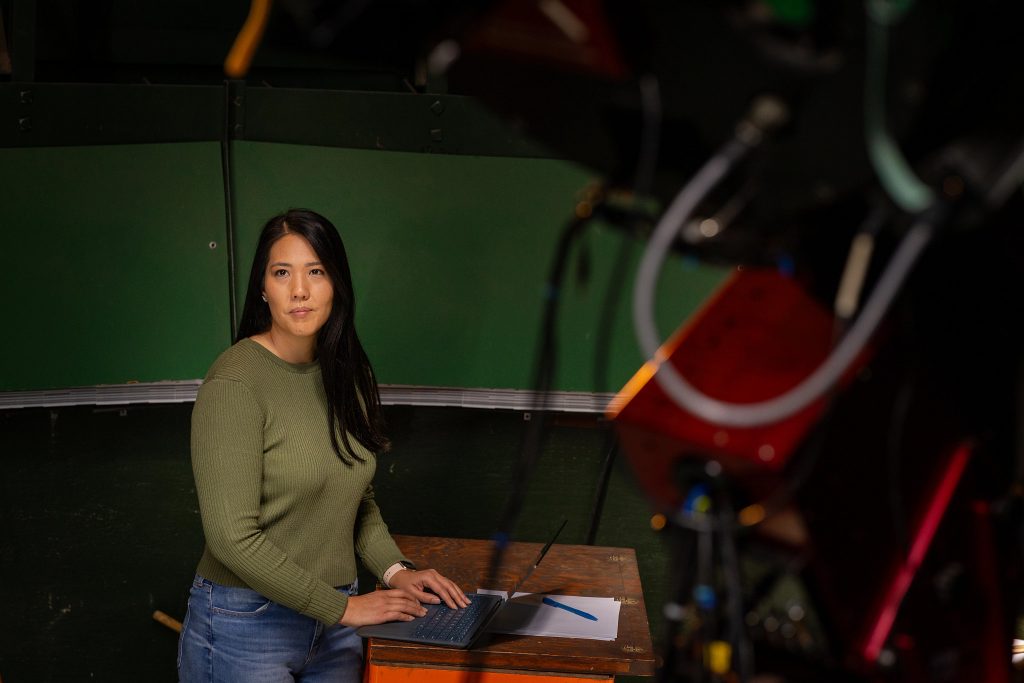

The team conducted a simultaneous observational survey with the JWST and HST to understand the size and color distribution of small TNOs. Morgan’s main role to date was to use computer programming to create a database of “fake TNOs” called synthetic objects. These objects have the same characteristics as the real TNO and help the team determine how small, how bright or dim, and what colors they can actually see. She calls the process “debiasing data.”

A teammate implanted the database of fake TNOs into images downloaded from the telescopes. Researchers then looked for TNOs and pulled out possible candidates. “So, if they are looking at the data and say, ‘Hey, I found this super, super faint object,’ I can ask, ‘Yes, but did you really? Because all the synthetic objects you pulled [were brighter than that object].’” Morgan says. “Having my synthetic objects in there will help us understand that maybe it wasn’t a TNO.”

Morgan will also take the lead on a paper regarding relatively bright, known TNOs and on a project measuring the colors of TNOs.

She credits her mentor, Trilling, and teammates for answering her many questions and helping her with her project. “Dr. Trilling has guided me through this whole process in understanding everything from the get-go,” Morgan says. “And when I was first developing these synthetic objects, I was able to go to other TNO and asteroid folks about how they would develop something like that because this is something they’ve done for debiasing their data. Everyone’s been kind and willing to make time for discussions and to further along this science.”

Principal Investigator on Hubble Space Telescope project

Recently, Morgan had a project accepted by HST and will be the PI. According to Trilling, that’s not typical for a first- or second-year grad student. He shared that Morgan didn’t hesitate to propose or lead the project. “Ana had not led a project like this before, but she learned—and won the proposal,” Trilling says. “That’s a ‘can do’ attitude.” She will be working with co-investigators from the US and Chile.

Morgan’s new project will dive even deeper into the world of TNOs and their size distribution. She explains that “the unique aspect of this project is our use of archival data from HST, spanning over a decade since 2009. Also, while our observational surveys concentrated on the ecliptic (the imaginary disc or plane describing the orbit of Earth around the sun), this project expands our scope to analyze TNOs from all over the sky.”

Morgan will again use her synthetic objects to debias databases during the TNO search and then follow search methods previously established for archived images, including those by her co-investigator—and former NAU post-doc—Cesar Fuentes from the Universidad de Chile.

A universe of questions

Morgan has landed in the right place. She is fueled by the curiosity of her fellow researchers. “There are just so many questions that can be asked, and in so many different regimes of all of the sciences here,” she says. “Being able to collaborate with other people in the department doing similar things with totally different objects—that’s the coolest part of what I get to do here.”