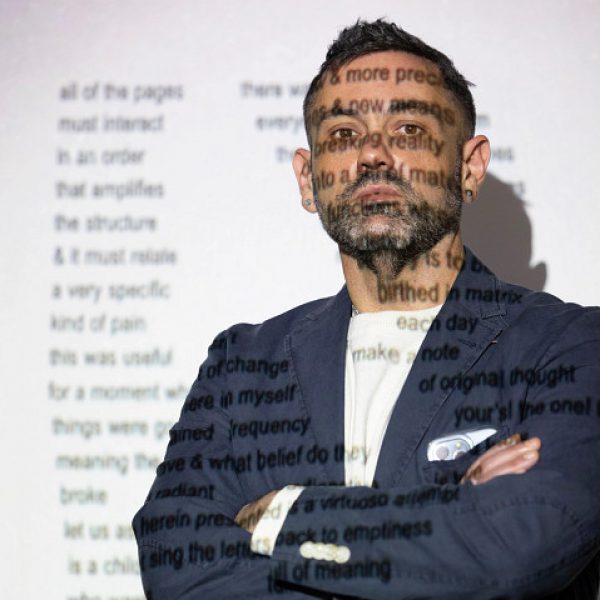

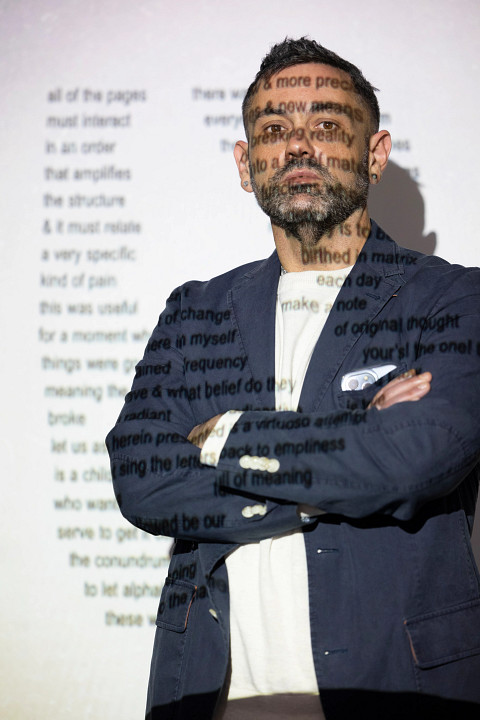

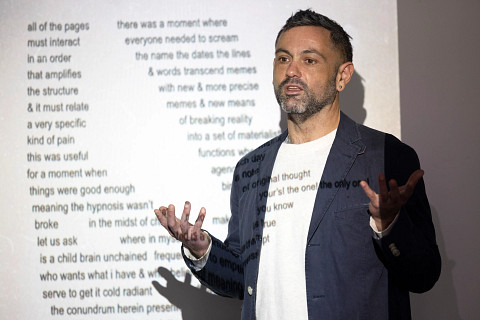

An Indigenous and Creole poet, traditional healer, and Kundalini yoga teacher, tanner menard opens their heart to radical syncretism.

As an NAU student pursuing a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing, tanner menard does not mince words. They’re unsatisfied with the way Indigeneity is often talked about in academic settings.

“If you’re in academia and you’re Indigenous, you’re supposed to use all this post-colonial dialogue to talk about things,” they said. “I learned it, but the language was like swords inside of my body.”

Born in Louisiana of Creole French, African, and Atakapa Ishak Nation heritages, tanner’s body holds a mixture of Indigenous and colonial influences, a blend that cannot be neatly divided into categories common to discussions of decolonization. The concept of “decolonization” itself seems incoherent to tanner; it’s a word that erases the reality of their existence.

“I’m trying to find words that I can use in an academic setting that are closer to my personal Indigenous understanding of the world,” they said.

One word that tanner has found is syncretism, which they understand as an openness to “mixing it up”—cultural reconciliation and “the old-fashioned art of forgiveness.” To tanner, syncretism puts the focus on heart-centered, positive connectivity.

“We need to start establishing relationships with one another. What’s happening now is we’re establishing a puritanical code of linguistic conduct between one another.”

They say the establishment of relationships can take many forms, from meditating during their yoga practice to sharing space in movement or dance. But most recently, tanner has focused on preserving the relationships embedded in their Indigenous language.

The loss of Indigenous languages has been a quiet consequence of colonialism, but plenty of folks are sounding the alarm. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, at least 65 Indigenous languages have gone extinct within the borders of the United States, with another 70 teetering on the brink. One of those is the tongue spoken by tanner’s tribe: the Ishakkoy language of the Atakapa Ishak Nation of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. “When Indigenous people lose their language, also lost is a cosmology of the people,” tanner said. “The recipes to those relationships with the land are broken and lost.”

To protect these relationships, tanner has created a series of children’s books called The Adventures of Ole’ Black Jack that will be published by That Painted Horse Press in 2022. The first installment is titled Ole’ Black Jack & the Clan Animals.

“I told a story about a character taking their niece and nephews to a lake where all of the clan animals come from,” they said. “The character explains a little about each animal and teaches the word in Ishakkoy.”

Don’t be fooled—there are more than just children’s language lessons in tanner’s series.

“I tried to hit as many different angles as I could in one very short story,” they said. “The book is actually meant for the parents or grandparents. It’s meant to teach the parents how to teach the children.” Thus, tanner’s straightforward plot harnesses the power of family connection to teach three generations at once.

In part, tanner became inspired to preserve Indigenous language when they received the Frederick J. and Alice W. Dockstader Scholarship for Indigenous scholars in the arts.

“I wanted to do something that would benefit my tribe down the road,” they said. “Personally, my feeling is that probably nobody is going to ever speak Ishakkoy fluently again. What is feasible is for people to learn relevant words and relevant phrases that can be used at tribal gatherings and taught to children.”

But tanner has not always been so focused on the power of words. In their twenties, they were primarily a musician and released ten albums of instrumental experimental music. Around the time they turned thirty, they became driven to learn more about their Indigenous heritage.

“I pursued learning about that for a number of years, but I needed to get back to the creative part of my life,” they said. “So I started writing poetry.”

Through poetry, tanner found a robust and like-minded community. They started a queer poetry salon for writers in Phoenix and connected with other Indigenous writers across Arizona. Among these was Sherwin Bitsui, renowned poet and professor in NAU’s MFA program.

“I met Sherwin in Flagstaff at the Northern Arizona Book Festival in 2017,” tanner said. “When I heard that he took the position at NAU, I messaged him and said I wanted to go to school there.”

Expecting to graduate in 2022, tanner has had a positive experience at NAU. They’ve found the atmosphere unrestrictive, conducive to their unique goals and interests: a place where they can push the boundaries of their own narrative and find the right words for their stories.

“There’s a lot of room to do your own thing here, even though I don’t think the way that everyone else thinks. I’m not going to tell a story in the way that is expected for an Indigenous author. I think there’s room for that at NAU.”