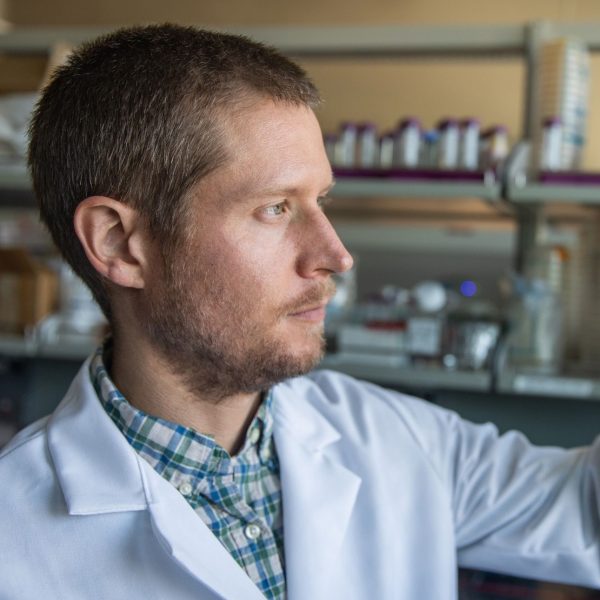

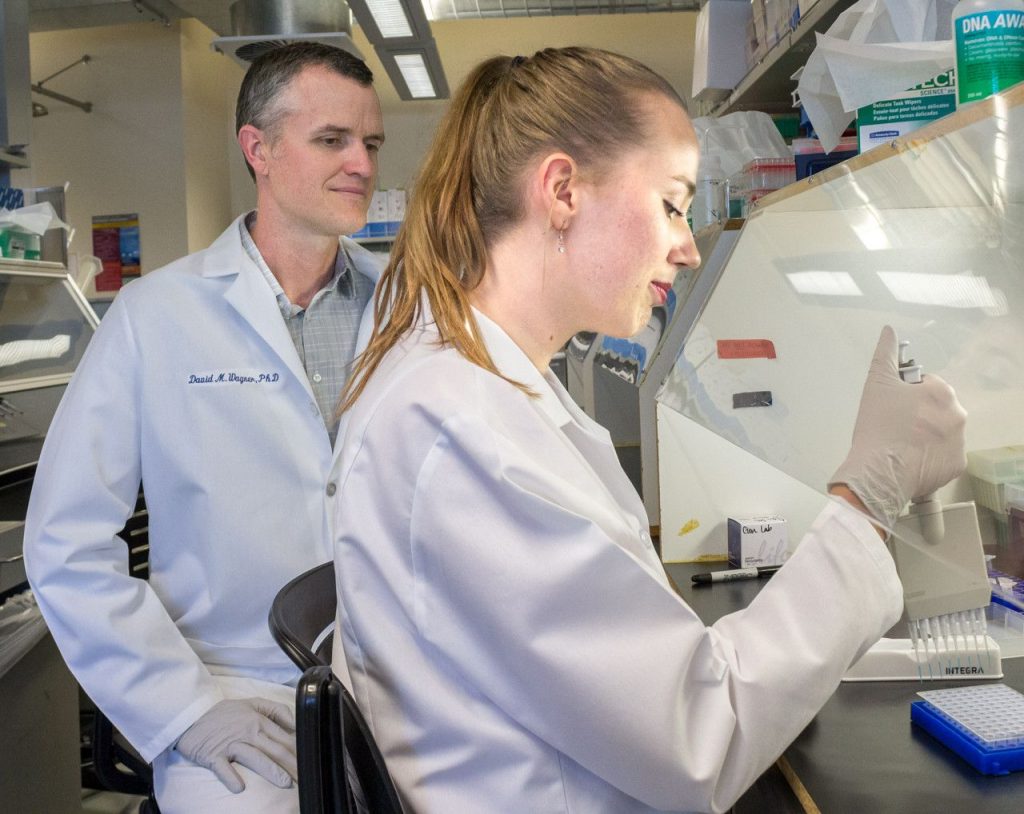

His twin passions for research and the outdoors—plus a sprinkling of serendipity—led Professor Dave Wagner to a career as a leading disease ecologist.

Professor Dave Wagner’s research focuses on some of the deadliest diseases known to the human race—including plague, melioidosis, and tularemia (rabbit fever). Many of the diseases he studies are potential biological warfare agents. As a disease ecologist, he uses genetic and genomic data to better understand the distribution, ecology, evolutionary history, and transmission patterns of infectious diseases.

Wagner is the Associate Director of NAU’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute (PMI) and currently serves as its Acting Executive Director. He has published more than 150 scholarly papers, won millions of dollars in grant funding, and gained recognition as one of the world’s leading experts on several deadly pathogens. But his career path was something he never expected.

“I would never have thought I’d be doing what I’m doing now. It was really because of the mentors I had, the opportunities I was given, and the hard work I put in,” he says.

Discovering an interest in research

Growing up in rural Illinois, Wagner didn’t think much about science. “I hear those stories about scientists who had a chemistry set when they were young, or who were always looking at things—but I was never really that kid,” he says. “I spent a lot of time outdoors. It wasn’t until high school that I had a brand-new teacher, right out of college, who was exciting and made physics interesting. So, I decided to be a high school teacher, too, teaching math and physics.”

A first-generation college student—his father was an electrician and his mother a homemaker—Wagner enrolled at Concordia University in Nebraska, where he pursued a BS in Secondary Education and a BA in Biology.

“In college, I was lucky enough to have a mentor who suggested I do undergraduate research, so I did wildlife research outdoors for three summers,” he says. “I just loved it, and I decided that’s what I really enjoyed—being out in the field. Physics wasn’t really for me. I was still working on my secondary ed degree, so I fulfilled my student teaching commitment. I learned a lot, but I didn’t love it as much as I loved research.”

At that time, if he’d been asked about his career path, Wagner says, “I thought I would be working for the Fish and Wildlife Service or the State Game and Fish Department.”

After earning both bachelor’s degrees, he spent some time as an AmeriCorps volunteer restoring wetlands. He applied to several graduate programs and ended up in the Zoology program at Southern Illinois University Carbondale studying wildlife biology.

“I liked the program a lot,” Wagner says. “I loved being outside, and I wanted to do that type of research. And then, in another stroke of luck, or maybe serendipity, I met a faculty member who was leaving SIU for a position as chair of the Department of Biological Sciences at NAU, so I ended up earning my PhD in Biological Sciences here, studying prairie dogs.”

That’s one of the big differences at NAU—there are lots of opportunities to get involved in research.

“As I was finishing up my doctorate in 2001, though, the prairie dogs I was studying started dying from the Black Death—the same plague that killed millions of people in Europe in the Middle Ages. I recognized an opportunity to go further with my research. I approached Paul Keim, at that time a Professor of Microbiology, who had developed a DNA fingerprinting system for diseases such as the plague, and we started collaborating. I would collect plague-infected fleas from the prairie dog die-offs, and his lab would perform the DNA fingerprinting.”

Anthrax attacks change career trajectory

“Of course, in the fall of 2001, that’s when the anthrax letters were mailed,” Wagner says. “Professor Keim’s lab went nuts because they had the best DNA fingerprinting system in the world. Samples were coming from the CDC and the FBI to be fingerprinted and investigated to see whether they were part of the attacks. As Keim’s lab took off, and the team needed to generate funding to continue its work, I started as a postdoc, writing papers and managing people. I’d developed grant-writing skills along the way and had already been awarded $100,000 in grants as a PhD student, so I wrote a lot of proposals to fund my own work, as well as other research being performed in the lab, for the next few years.”

Wagner joined NAU as an Assistant Professor in 2005. From there, his career continued its vertical trajectory, and he was promoted to Associate Professor in 2011 and Professor in 2016.

Since then, he has expanded his research to include a wide range of pathogens and diseases, developing assays for diagnostic testing, leading important new studies, and collaborating with scientists all over the world. But the plague remains one of his favorite diseases. “I still find plague fascinating because of its historical context,” he says.

Among many other research interests, Wagner is currently involved in developing DNA capture and enrichment methodology, with the goal of getting all of a pathogen’s DNA. “Using the teeth from a human skeleton with the Justinian plague—from about 1,500 years ago—we were able to capture just the pathogen’s DNA and generate a full set of genomic data.”

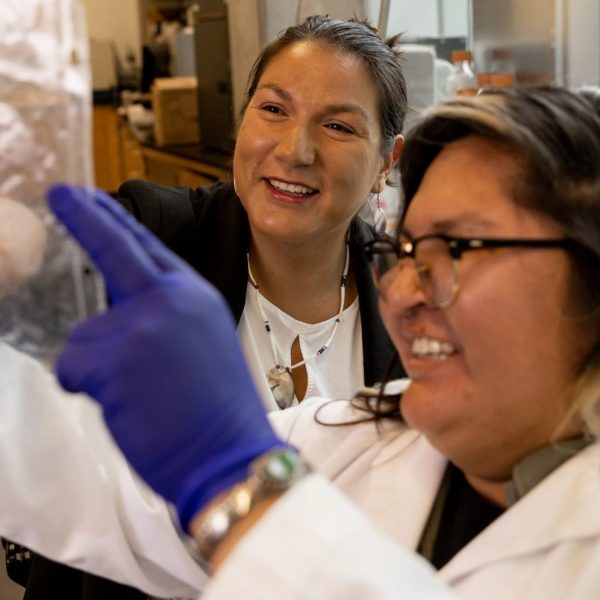

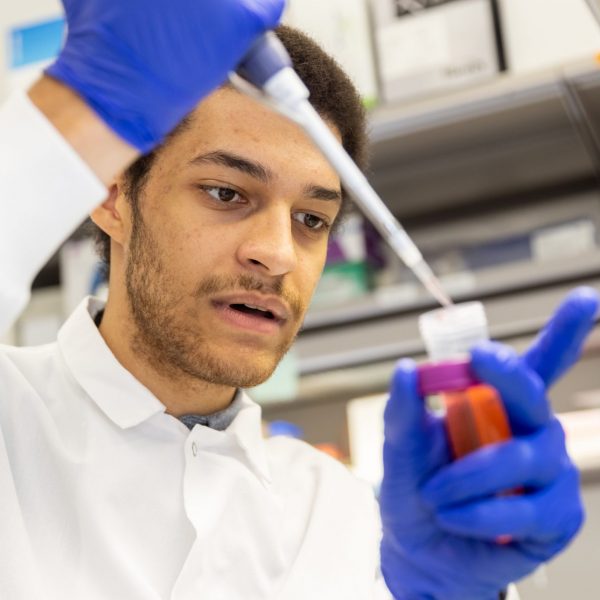

Mentoring a priority for Wagner

Wagner is a research mentor for PMI’s undergraduate research program, which typically trains 35–40 students every year. “I usually have about ten undergraduates in my research group,” he says. “We’re really proud of that program because it’s rigorous and intense. But we turn our students into colleagues. They come in not knowing what’s going on, a little timid, but we could put them up against master’s level students pretty much anywhere when we’re done training them. They know what they’re doing. They know how to talk about the science and present it. One of the great joys of the job is mentoring the new round of scientists who are going to take over.”

Wagner’s advice? “You never know where you’re going to end up in life, so follow opportunities as they come up. Just try things out; try different things. I tried a couple different majors until I found something that stuck. I think it’s really key for undergraduates to seek out opportunities to work in your field if you can. That’s one of the big differences at NAU—there are lots of opportunities to get involved in research. Just keep an open mind.”