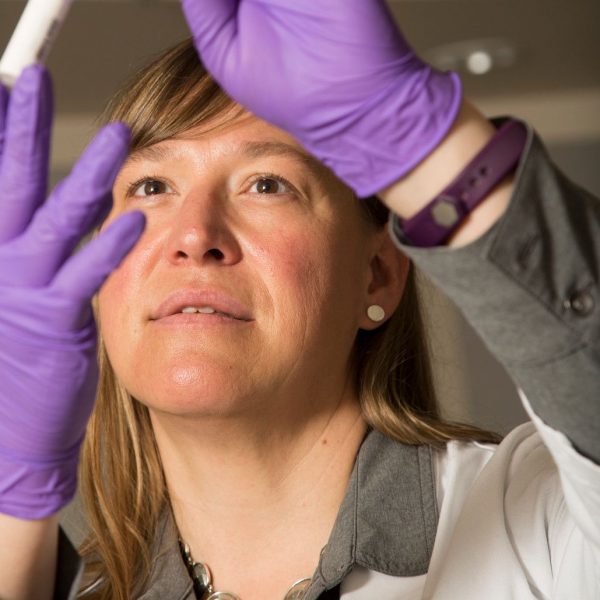

Teacher and scholar Bridget Barker explores the environmental sources of fungal pathogens to prevent exposure and infection.

Associate Professor Bridget Barker of NAU’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute first became fascinated with plants, starting her journey studying botany. “I was really interested in plant pathology, and I’ve always been interested in the interaction between species,” Barker says. “So I started out working on plants, and I was very interested in the co-evolutionary processes between plants and their insect herbivores. I’ve always been fascinated by evolutionary trade-offs: for example, how a plant adapts and creates a volatile chemical that’s a toxin to certain insects that chew on its leaves.”

Her academic interests grew to include the ecology and evolution of a wide array of organisms, eventually leading to fungal pathogens—which are not nearly as well understood as bacterial or viral pathogens.

Barker earned a BA in Botany and an MS in Organismal Biology and Ecology from the University of Montana, then worked for the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural Research Service in Prosser, Washington as a lab technician. “I had a great mentor at the USDA,” she says. “He told me I really wasn’t a technician, and that I needed to get my PhD.”

As a girl growing up among farmers and ranchers in Billings, Montana, Barker’s highest aspiration was to be a veterinarian because of her love for horses. That early impulse to be a healer—along with persistence, an innate sense of curiosity, and a strong drive to be successful—led her to ultimately become a biologist, disease ecologist, and geneticist studying the pathogens that cause Valley Fever, a potentially deadly, dust-borne fungal disease increasingly common in the desert Southwest.

Barker moved to Tucson, securing a position at the University of Arizona (UA) working in the lab with researchers studying the genetics of Coccidioides immitis and C. posadasii (cocci for short), the pathogens that cause Valley Fever. But soon, realizing how much she wanted to help solve the mysteries surrounding the pathogens herself, she earned her PhD in Genetics at UA, supported through a prestigious IGERT (Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship) Fellowship in Comparative Genomics from the National Science Foundation.

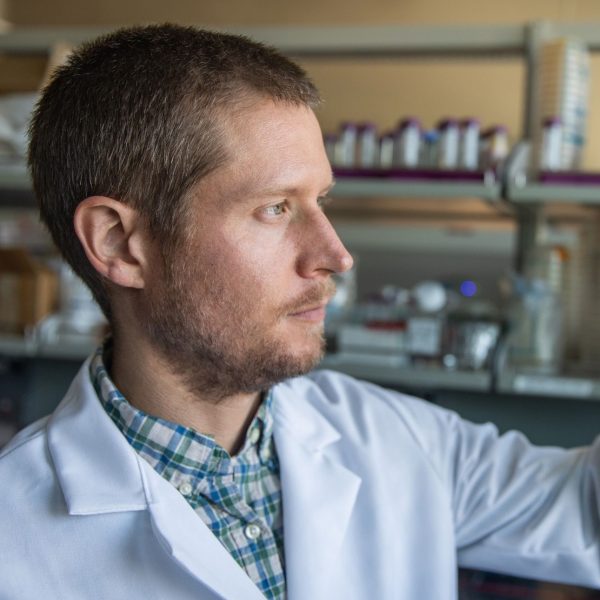

After a postdoctoral fellowship and a stint as research faculty at the University of Montana, Barker came to Flagstaff in 2013 as an Assistant Research Professor both at NAU and at TGen North Clinical Laboratory. In 2016 she joined NAU’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute (PMI) as a research-intensive tenured Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and was subsequently promoted to Associate Professor. Since then, she has been building her career with research focused on the ecology and population genetics of cocci and detecting cocci in the soil.

By developing better methods of detecting the fungus linked to Valley Fever in the environment and identifying ways to reduce exposure, we can prevent people from being infected.

Making a difference in Arizona and beyond

One of Barker’s concerns is with health disparities affecting disadvantaged populations, who are at risk of exposure to Valley Fever yet may not have equal access to healthcare. “Delayed diagnosis is a risk factor for severe disease,” she says. “The lack of access to healthcare as well as specialists can delay treatment, increasing mortality risk. Additionally, workers in occupations such as construction, farming, and landscaping are more likely to be exposed to high levels of fungal spores, which increases the likelihood of severe disease. By developing better methods of detecting the fungus linked to Valley Fever in the environment and identifying ways to reduce exposure, we can prevent people from being infected.”

Beyond Arizona and the Southwest, Barker explains, Valley Fever affects communities in some of the most impoverished regions of North and South America. “I work with researchers in Mexico, Venezuela, and Brazil to look at similar questions in these regions, as well as fungal infections more broadly. These diseases cause a great deal of morbidity (illnesses or unhealthy conditions), including severe facial deformities, which can permanently impede a person’s ability to work and thrive.”

Barker wants to make a difference with her work. “In the short term, we hope to increase awareness—both for the public and medical professionals,” she says. “The more people are aware of Valley Fever, the more likely testing will occur before the onset of severe disease. In the long term, we would like to deploy a monitoring system to detect higher risk and alert the public and clinicians on a weekly basis. I believe that this will increase early detection and also help our research in understanding the impact of climate change on fungal diseases, including Valley Fever.”

Targeting environmental sources of dust-borne spores

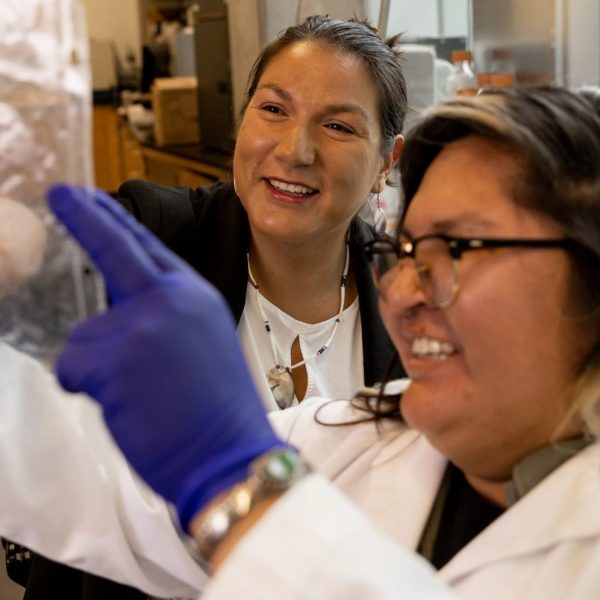

Among her many projects, Barker is collaborating with Assistant Research Professor Anita Antoninka of NAU’s School of Forestry to determine whether biocrust restoration can reduce dust-borne cocci spores, which are the causative agent of Valley Fever.

“Targeting the environmental source of Valley Fever is critical, as the disease is not passed from human to human,” Barker says. “The fungus grows in the soil, and people get sick from breathing in the fungal spores from the environment. We are looking at the effect of biocrust restoration on the prevalence of the organism in soil.”

But it’s not an easy fix, and Barker has learned some important lessons. “The desert Southwest is incredibly beautiful and restoring soils in the area can have multiple benefits. This area of research is novel and exciting, but difficult to fund! I think the desert has taught me resilience and patience.”

I really love teaching small capstone classes with upper-division students because it’s so much fun. And I learn a lot by teaching those classes, too. Because they’re challenging. Those are the students who are going to ask you really tough questions.

Teaching and mentoring an important part of the job

Although Barker’s primary focus is on her research, she says that when she worked as research faculty without teaching, she missed sharing her knowledge. “It just wasn’t for me. I wanted to have grad students and undergrads. I wanted to be able to have more of a mentoring role. I really love teaching small capstone classes with upper-division students because it’s so much fun. And I learn a lot by teaching those classes, too. Because they’re challenging. Those are the students who are going to ask you really tough questions.”

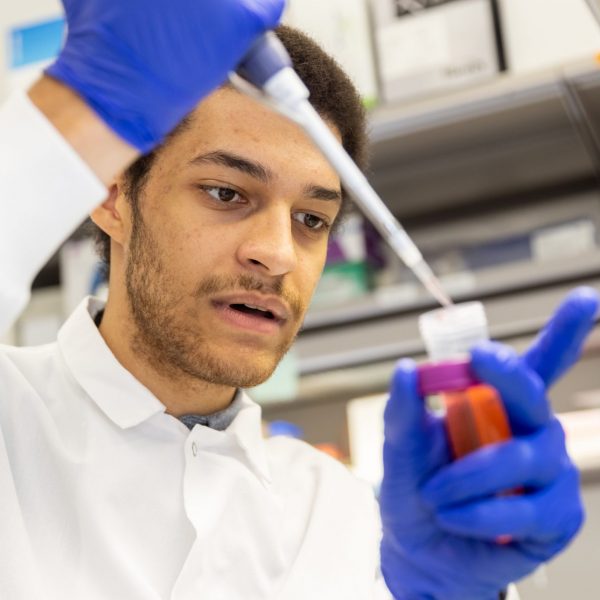

Barker teaches courses including BIO 346: Advanced Microbiology; BIO 471C: Microbial Ecology; and BIO 485: Undergraduate Research. She mentors and trains undergraduates in her lab, which is a collaborative academic workplace.