Off to Ole Miss: Diedre’ Goodluck’s MPH experience in toxicological science

Mike Anastario, assistant professor in health sciences, builds capacity for mentorship into his research projects, allowing his student, Diedre’ Goodluck to assist him with lab work at the University of Mississippi. Goodluck (Diné) is a 2nd year master in public health (MPH) student approaching her education as a way to lead health equity research in her community.

The Center for Health Equity Research (CHER) celebrates the power of mentorship and the impact of diverse perspectives in advancing public health research. We strive to guide, empower, and equip students throughout their academic careers and into the health equity workforce.

Anastario’s work in harm reduction for Tribal communities

Anastario focuses his research on harm reduction strategies for people who inject methamphetamine (meth) in Tribal communities. Native Americans have one of the fastest climbing rates of drug overdose deaths involving stimulants. Meth injection is associated with excess disease burdens that may be amplified by exposure to environmental toxicants like metals that contaminate meth injection preparations. Through preliminary work, he’s shown that environmental harm reduction interventions are needed to reduce the injection of metal-contaminated meth injection preparations. As the meth epidemic permeates rural communities, unique challenges highlight the importance of using innovative assessment approaches.

Anastario tends to go directly to the source, looking and listening for problems that individuals are facing and talking about. He feels he learns more about what communities need by meeting with people face to face and simply asking.

“At this point, I’ve formally interviewed over 100 people who inject meth,” he explained. “I’m trying to translate everyday hypotheses that I hear into scientific inquiry.”

“How on earth do you come up with your hypotheses?”

Some of Anastario’s peers have questioned his direct approach, to which he responds, “I just talk to people, and try to convert what they think is happening in their environment to scientific inquiry, and when I look for answers in the literature, sometimes the science just isn’t there.”

His approach opens the door for his research questions to evolve, sometimes change drastically, to develop studies in tandem with the desires of the people he’s listening to.

This approach ultimately brought him to his current question: how can we develop the science of environmental harm reduction for people who inject meth and other substances?

Goodluck’s path to Anastario’s research

Goodluck began her MPH program directly after earning her BS in Interdisciplinary Studies – Public Administration at Northern Arizona University (NAU). This allowed her to gain insight on how federal policies directly impact Native Americans – specifically inequities in health care and social determinants of health.

In 2023, Goodluck was inducted into the Native American Student Webinar Advisory Coalition (NASWAC) inaugural cohort of scholars. NASWAC is a Center for Native American Cancer Health Equity (C-NACHE) initiative that brings Native students’ voices to the table to develop engaging webinars on emerging cancer health equity research.

Joining NASWAC was not Goodluck’s first interaction with CHER; she took a graduate course with Samantha Sabo, CHER associate director and professor in health sciences, that offered a class assignment that created the opportunity to network with Dr. Donald Warne, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health.

During the interview, Goodluck asked him if his Indigenous background had influenced his approach to research in public health. His answer inspired and reoriented her:

Goodluck recalls Dr. Warne answering her question by explaining that he was born into it. It wasn’t something that he learned in a textbook. It wasn’t something that he learned in a program. He was born into it–just like she was.

She knew that meant committing her educational journey to her people back home on the Navajo Nation, or even her home community of Coalmine Mesa, AZ. And she could do that by exploring each facet of health equity research, starting with an offer to fly to Mississippi in late July from her mentor, Anastario.

Off to Ole Miss

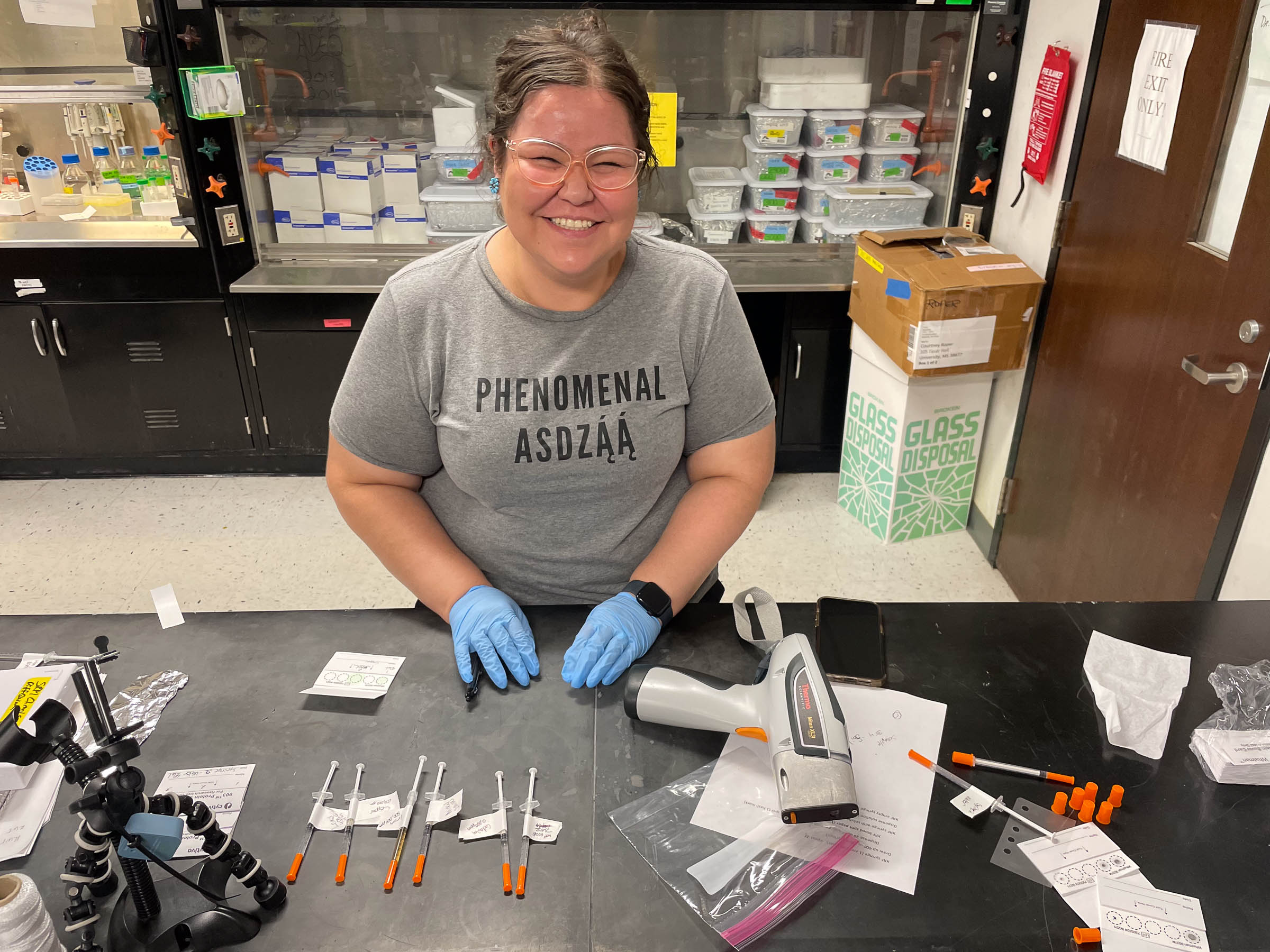

Goodluck’ agreed to join Anastario on a week-long trip to the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) to conduct research work in colleague Courtney Roper’s lab to gain experience in a lab science setting.

Roper is an assistant professor of environmental toxicology and assistant research professor in the Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and joins Anastario in The JPB Environmental Health Fellowship Program.

Facilitated by the Health Fellowship Program, Anastario and Roper led the research session together hoping for two outcomes:

- Test and develop best-practice methods for syringe filtration of metal

- Pilot a training model tailored to Native American students

Roper’s doctoral students participated in Anastario’s study for the week, testing filtration methods and devices in hopes of learning best-practice methods for reducing harmful toxicants from meth injection preparations.

The immersive exposure provided Goodluck with the opportunity to dive into the work behind data collection.

Learning about new environments

Goodluck spent the week helping to conduct the experiment. The first two days consisted of testing environmental factors in the lab that could affect results and conducting reliability tests. She learned how comprehensive – and vital – those parts of a study can be. She laughed and mentioned that during those first few days, she had non-stop questions for the other students.

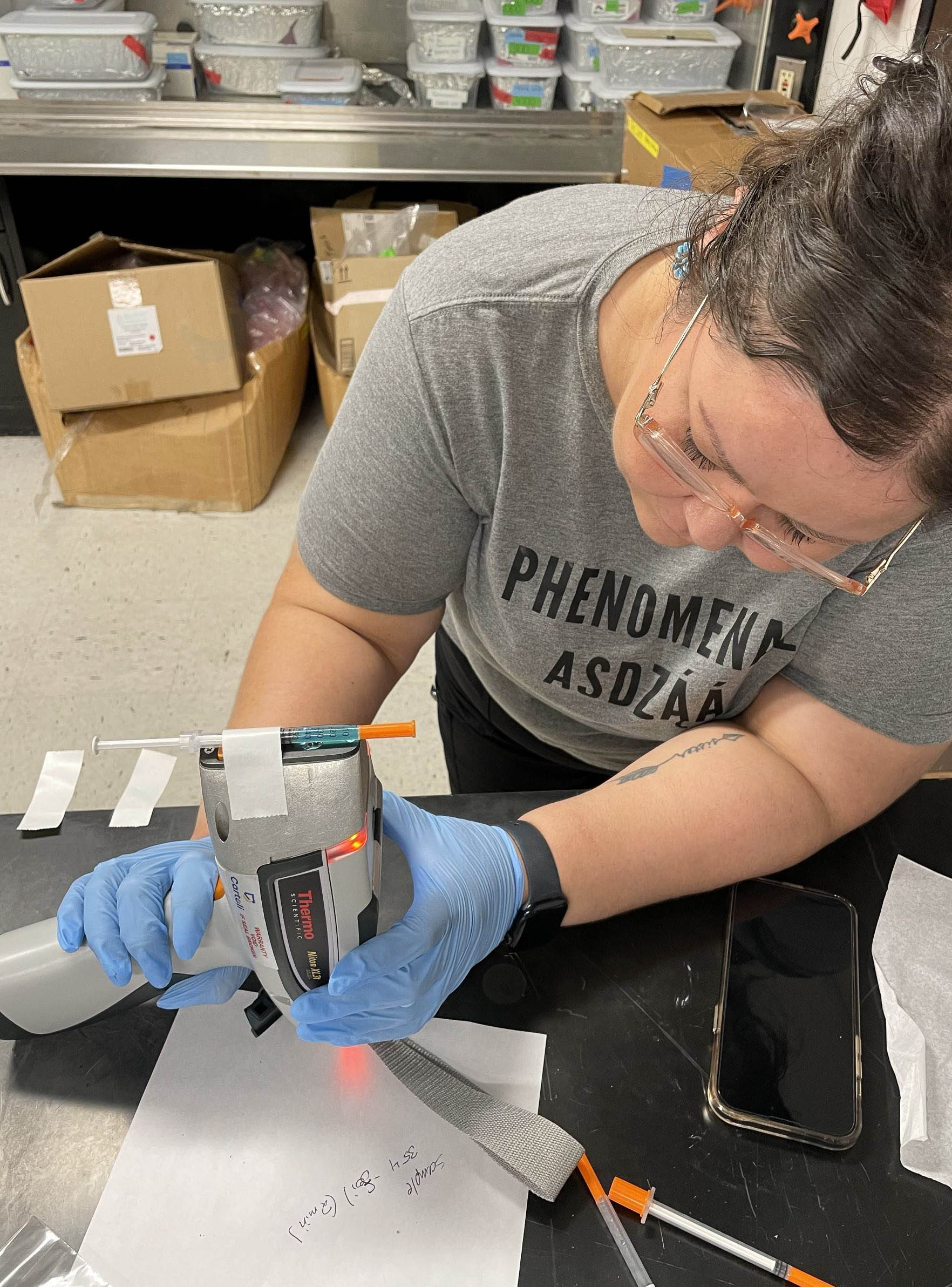

After the initial tests, she was trained with an instrument called a portable x-ray fluorescence device. Anastario reported that Goodluck was trained on the instrument and quickly began processing samples. After working with the device, she plans to incorporate the device as a part of one her research questions for her future PhD dissertation, which she plans to pursue following the completion of her MPH, next May.

“Diedre’ operated the portable x-ray fluorescence for the duration of the experiment. That was great because while she did that, I was free to pay attention to the statistical modeling and Dr. Roper could pay attention to the metal mixtures,” added Anastario.

“The experiment moved quickly. Diedre’s assistance with the portable x-ray fluorescence helped us be more efficient. That’s a direct benefit to the study, and one of the reasons that she will co-author the manuscript that is currently being developed.”

“I knew going into the program that I wanted to help my community, and that week shaped my entire perspective,” shared Goodluck.

Goodluck returned to Arizona with at least three new benefits:

- Co-authorship on a peer-reviewed study

- Experience with a non-invasive approach to exposure assessment

- A clearer vision for the type of work she wants to do

Community-based research

Toward the end of the week, Goodluck expressed to her mentor that while she loved the topic they were studying, she felt that she was now ready for fieldwork and was excited to participate in the face-to-face component of this type of research. Anastario wasn’t surprised during their conversation and recognized her ease in communicating with new colleagues in the lab.

He counseled her that time spent learning what you don’t like to do is not wasted, and talked with her about how this lab work will prove beneficial to her. He shared that if she plans to lead a study in her community, she’ll bring an understanding of what happens in a lab, and that would affect everything.

“It sort of opens up the black box,” described Anastario. “Even though you don’t want to work in the black box, you have a greater understanding of research and can integrate what you’ve learned into your own practice as an educated professional who will likely collaborate with bench scientists, contract their time, understand their unique practices and ways of operating in the world.”

Relative connection

One element of the research that Goodluck wasn’t prepared for was her emotional response to working with samples from her Native American relatives.

While she recognized that these samples did not belong to her direct family members, she felt as connected with them as if they were.

The samples were generated to evaluate metals that Anastario had detected in injection preparations in the field, and Goodluck recognized that the significance of the data went beyond research, acknowledging the sacred connection to community and purpose.

“As I was testing them, that’s all that was going through my mind,” Goodluck said. “Being from a Native American community, many of us know somebody who has been affected by substance use disorder or chronic health conditions.”

Connection built into curriculum

Goodluck’s connection to the study is exactly why she is working diligently in her MPH program and bringing her knowledge and lived experience along with her.

“I’ve been in programs before where I was usually the only Indigenous person in the class, or I had to really tailor the work to suit an Indigenous perspective,” Goodluck said when asked about challenges she’s faced in her public health journey.

She noted that her current MPH program is different from that experience.

“In this program, [Indigenous perspective] is encouraged, and the professors go above and beyond to make sure that their Indigenous students are benefitting from the program.”

Diverse Perspectives and Innovation

Anastario highlights the role of diverse perspectives in driving innovation: “Integrating different perspectives and diverse people into research teams is what leads to innovation in research.”

Knowing this, he is currently trying to get more support for training models that support first-generation and underrepresented students through hands-on experience with technical aspects of public health research, based on the training model they piloted with Roper’s students and Goodluck.

Future directions and training models

Students come from a variety of backgrounds, some with parents and family members that obtained postgraduate and postdoctoral degrees, and some who have no experience with higher education. Anastario wants to offer opportunities to students who have fewer resources at their disposal while navigating bioscience research programs by integrating them into high caliber research projects.

“I want to see more programs designed for students who don’t necessarily have a great deal of social capital in this area,” expressed Anastario.

“They’ve shown academic prowess, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re going to skyrocket into biomedical research. It’s a strange environment, and I think we need more mentoring models that are specifically designed for students from groups that are underrepresented in biomedical, behavioral, and social sciences.”

Anastario hopes to implement this type of training model throughout his research and plans to develop a model that can be applied widely to increase representation of Native American researchers in groundbreaking scientific discovery.

“I’m very supportive and hopeful. This work and training model are important and will benefit a lot of students. I want to help in any way that I can.” echoed Goodluck.

“I encourage more Indigenous students to get involved. We need more Indigenous representation, ensuring that we are actively reclaiming narratives that honor truth and cultural relevance.”

The MPH – Indigenous Health program is designed to train the public health workforce through teaching, community service, and scholarship to improve public health through practices, policy changes, leadership/management work, and creating interventions in Arizona with a focus on rural, Tribal, and border communities. We encourage you to explore the program and make change in the world of Indigenous public health.