June 2021 Faculty Research Spotlight

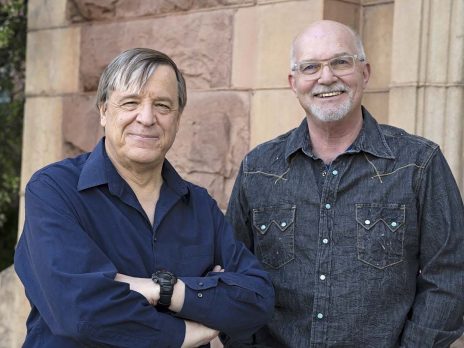

Dr. Leszek Pawlowicz and Dr. Chris Downum | Breakthrough in Archaeological Applications of Machine Learning

Typologies are central to archaeology. Everything from spear points to pottery designs to sandals to societies have been classified into types. Anthropologist Julian Steward in 1954 even proposed a typology of typologies, writing an article called “Types of Types.” I cannot think of many archaeological endeavors that do not use some form of typology. This is necessary, because typologies reduce complex and otherwise baffling variation into a limited number of comprehensible categories. They help us make sense of what author Henry James once called “the intolerable buzz of reality.”

Typologies are central to archaeology. Everything from spear points to pottery designs to sandals to societies have been classified into types. Anthropologist Julian Steward in 1954 even proposed a typology of typologies, writing an article called “Types of Types.” I cannot think of many archaeological endeavors that do not use some form of typology. This is necessary, because typologies reduce complex and otherwise baffling variation into a limited number of comprehensible categories. They help us make sense of what author Henry James once called “the intolerable buzz of reality.”

But how well do typologies work? Do they oversimplify, and thereby potentially mislead? Do archaeologists apply them consistently? How does a person learn a typology? Do typologies change through time, and if so, by how much? What are the rules of typology, and who documents and enforces them? These and other related questions have intrigued archaeologists since the beginning of archaeology. They are also some of the questions that I and Anthropology adjunct faculty Leszek Pawlowicz recently set out to explore, using a form of Artificial Intelligence known as machine learning.

Just a quick note on Leszek Pawlowicz and his extraordinary abilities: In 2015, I started collaborating with Leszek on a variety of field projects. Leszek, who has a Ph.D. in Materials Science from MIT, is a phenomenal technical and methodological expert. He is exceptionally good at everything he does, and I have never been able to offer him a computer- or technology-related task that he couldn’t solve. During our collaborations, we discussed the possibility of using the emergi ng field of computer vision and artificial intelligence (AI) to test and refine archaeological typologies. Leszek had initially been interested in training a computer to classify projectile points. Though I can’t remember the exact details, we eventually settled on what was to me a very intriguing experiment: Could a computer be trained to “see” and classify the complex painted designs on ancient black-on-white pottery? We thought it would be interesting to try, and we agreed that a particular northern Arizona pottery ware, Tusayan White Ware (c. 800 to 1300 CE) would be an ideal candidate.

ng field of computer vision and artificial intelligence (AI) to test and refine archaeological typologies. Leszek had initially been interested in training a computer to classify projectile points. Though I can’t remember the exact details, we eventually settled on what was to me a very intriguing experiment: Could a computer be trained to “see” and classify the complex painted designs on ancient black-on-white pottery? We thought it would be interesting to try, and we agreed that a particular northern Arizona pottery ware, Tusayan White Ware (c. 800 to 1300 CE) would be an ideal candidate.

In a fun bit of unfunded research, Leszek and I recruited four archaeologists with decades of experience classifying Tusayan White Ware. Each of the four was given a set of more than 3,000 digital photographs of broken pieces of pottery (potsherds, or simply, sherds) to classify into existing types. (Full disclosure: one of the archaeologists was me, though I still do not know which of the anonymized subjects A, B, C, and D I represent.) Leszek created a program that automatically recorded the archaeologists’ responses and wrote them to a database. This database of sherd classifications was then refined to include only the consensus sherd specimens that at least a plurality, if not a majority, of the four archaeologists agreed upon. The consensus images then became a training set to teach the computer how to classify pottery, using a programming approach based on Convolutional Neural Networks, or CNNs.

The results of our experiment were remarkable. We found that the computer can classify complex pottery designs as well as a human, using only digital images of artifacts, and it can do so with the same result every time. The computer out-performed two of the expert archaeologists, and essentially tied with the other two. Not only that, the computer was able to do something that most people struggle with: Reveal the exact features used to classify a potsherd into a particular type. It did this by creating a heat map image of each sherd, highlighting with warm and cool colors the specific areas on the sherd that led to the computer to its decision, or was irrelevant to its “thoughts.”

Even more exciting for me, Leszek was able to utilize a method to identify sherd matches or, using the German word for one’s lookalike, “doppelgangers.” Using statistical measures of similarity in hyperdimensional space, the computer can search through thousands of sherd images in a matter of seconds to find the sherd or sherds that most closely match other sherds. To my knowledge, this is unprecedented in archaeology, and it is for me a kind of archaeological holy grail, something I have been seeking off and on since the early 1980s. For the first time, we can now apply what is basically a facial recognition approach to matching one sherd with another. This has tremendous implications for precisely dating archaeological pottery, finding pieces of the same broken pottery vessel scattered across an archaeological site, or possibly even identifying an individual ancient artisan.

Even more exciting for me, Leszek was able to utilize a method to identify sherd matches or, using the German word for one’s lookalike, “doppelgangers.” Using statistical measures of similarity in hyperdimensional space, the computer can search through thousands of sherd images in a matter of seconds to find the sherd or sherds that most closely match other sherds. To my knowledge, this is unprecedented in archaeology, and it is for me a kind of archaeological holy grail, something I have been seeking off and on since the early 1980s. For the first time, we can now apply what is basically a facial recognition approach to matching one sherd with another. This has tremendous implications for precisely dating archaeological pottery, finding pieces of the same broken pottery vessel scattered across an archaeological site, or possibly even identifying an individual ancient artisan.

The research is reported in the June issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440321000455, Open Access) . Because we are the first archaeologists to succeed at using machine learning to classify complex design images on pottery, the article has attracted interest from researchers around the world. We are currently discussing collaborations with archaeological research groups in Europe, involving a variety of artifact types ranging from pottery to jewelry. The project was reported on by the New York Times (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/25/science/archaeologist-neural-network-study.html), the influential online tech journal ArsTechnica ( https://arstechnica.com/science/2021/05/archaeologists-train-a-neural-network-to-sort-pottery-fragments-for-them/ ) and will be featured in an upcoming segment on WXVU of Cincinnati Public Radio ( https://www.wvxu.org/post/archaeologists-beginning-leave-tedious-work-sorting-computers#stream/0). Leszek and I are currently working on additional articles that will explore visualization of archaeological typologies through reduction of hyperdimensional space to two or three dimensions, and a future project will examine how archaeologists, potters, and machines agree or disagree on pottery classifications.

Chris Downum

Learn More About the Ceramic Analysis Lab