By Madeleine Levesque

November 4, 2024

Madeleine Levesque is a former NAU and current ASU undergraduate student studying anthropology and French. She is interested in medical anthropology and global health, hence her interest in the health and hygiene items found at Apex. She hopes to take a gap year and then head to medical school to become a physician after graduation. Despite the change in schools, she is excited to continue to research all of the awesome things found at Apex.

Check out Madeleine’s Interns-to-Scholars Poster, Notions of Health and Hygiene in the Depression-Era United States: Apex, Arizona, for more information on her research. And for more about Apex or the Apex, Arizona Archaeology Project, visit our website or email Dr. Emily Dale at emily.dale@nau.edu.

Do you apply deodorant daily? Brush your teeth or use mouthwash? So did the occupants of the Saginaw-Manistee logging camp of Apex, Arizona, even in the 1920s and 1930s. Today, we probably hold these practices near and dear as the indisputable hygienic code of conduct and may feel uncomfortable when people fail to follow suit. But where did our Western notions of health, sanitation, and hygiene come from? And why are they so pervasive?

Ew…Do You Guys Smell That?

The turn of the 19th century was a time of growing health science research, especially for gastroenterology and germ theory. A major GI fad during the Depression era was curing the ‘American disease’ of constipation, seen as being caused by the increasingly sedentary and dietarily over-indulgent lifestyle of Americans. Laxatives were extremely popular—they were marketed to purge the bowels of built-up fecal matter, which was seen as a cause of body odor.

At Apex, there are a variety of laxatives. Glass shards from bottles of Dr. Caldwell’s Pepsin Syrup, Citrate of Magnesia, Charles H. Fletcher’s Castoria (“the kind the baby cries for”), and Petrolagar (the company produced a 1932 pamphlet titled “Habit Time of Bowel Movement”) reflected that Apex occupants likely had a laxative of choice and purchased them individually, rather than one brand being supplied by the company store.

Body odor was established as unhygienic once Americans accepted the notion that it originated from the presence of bacteria and germs. Mouthwash, toothpaste, and deodorant were thus marketed as effective combatants against this affliction. “Halitosis,” or bad breath, was invented in the 1920s by Listerine as a treatable medical condition to sell mouthwash. A Pepsodent toothpaste tube, a Listerine mouthwash bottle, and a Lavoris mouthwash bottle were all found at Apex.

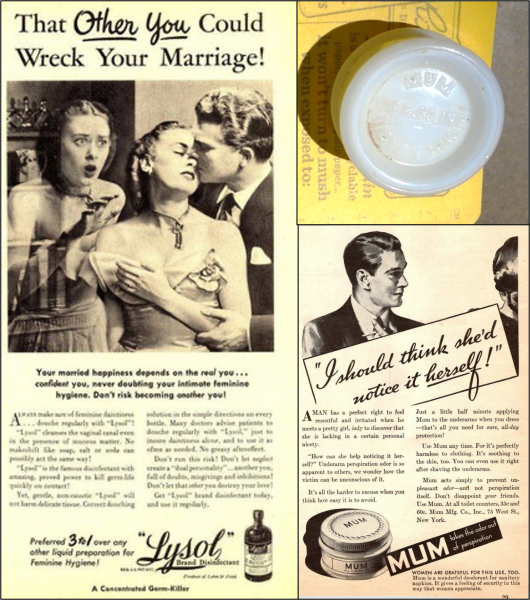

Many of the hygiene products at Apex suggest women were especially worried about BO. Since routine bathing would have been uncommon or inconvenient at Apex, as there were no showers nor running water, two “Mum” brand milk glass antiperspirant deodorant jars suggest an alternative to relieving body odor. Mum was the first company to manufacture deodorant and marketed their product at women to reduce foot, armpit, and genital odors. Unfortunately, the fear of body odor also extended to feminine hygiene. Women were marketed Lysol douches—yes, Lysol, like the bleach—to eliminate vaginal odor (and, incidentally, as a spermicidal). As only one Lysol bottle has been found at Apex, we posit this brand of bleach was used differently than the numerous Clorox bottles found at the site. We might see that now and cringe, but scented, odor-eliminating feminine douches are still very popular today!

Look at Her Hairy Legs!

By the Great Depression era, Victorian standards of beauty began phasing out, ushering in the era of the “flapper girl” and more liberal fashion. Typical 20s and 30s flapper fashion featured sleeveless, slinky dresses where the arms, armpits, and legs would be exposed, creating demand for women to keep these areas clean-shaven and ‘non-masculine’. Men’s hair hygiene also became important as unkempt facial hair was seen as slovenly. Dirt, lice, sweat—and now odor and bacteria—were known to live in facial hair. Thus, being clean-shaven was a must for men to attract women and get a good job!

At Apex, various shaving paraphernalia were found. A Gem “butterfly” razor could be used for at-home shaving, whereas the previous norm was to go to a barbershop and be shaved with a straight razor. Ads reveal that Gem razors cost around $1.00 in the 1920s, or around $18.00 today. This shift to shaving being accessible at home set the expectation that people were to include shaving in their personal hygiene routine. A shaving mug, safety razor blades from the Valet and Paris companies, and a Lifebuoy shaving cream tube were also found at Apex.

Conclusions

Today, American consumers are inundated with advertisements for dermatologist-approved cosmetics and “clean girl aesthetic” content on social media. Shaming of people who are not seen as clean, have body odor, or have unkempt appearances is common, accepted, and even encouraged. These are all very powerful social forces that keep us hygienically ‘in-line.’ Despite Apex being largely isolated from any major city of town, it seems that emergent ideas about cleanliness reached them. Residents may have brought these ideas with them, or learned from magazine advertisements or in phone calls with city-dwelling friends and family. Interestingly, these hygiene and personal grooming objects were found across the site, at the laborer’s bunkhouse, worker family housing, and management housing, indicating that 1920s and 1930s ideas of health and hygiene cross-cut class, ethnicity, and gender.

Mystery Lids!

At Apex, we have discovered two ferrous, internal-thread lids, one for a jar and one for a small-mouthed bottle, with an impressed logo that appears to depict a dolphin leaping through some waves. Searches for the logo have turned up nothing, beyond a dead-end about the sale of canned dolphin meat in the 1930s (!). If you recognize this logo, let us know!

Sources

Anon. Alleviating Body Odors. National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object-groups/health hygiene-and-beauty/alleviating-body-odors.

Anon. Gillette U.S. Service Razor Set. National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/nmah_1153449.

Clark, Laura 2015 How Halitosis Became a Medical Condition With a “Cure.” Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/marketing-campaign-invented-halitosis-180954082/

Eveleth, Rose 2013. Lysol’s Vintage Ads Subtly Pushed Women to Use Its Disinfectant as Birth Control. Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/lysols-vintage-ads-subtly-pushed-women-to-use-its-disinfectant-as-birth-control-218734/

Smithsonian Institution. Hair Removal. Smithsonian Institution. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/health-hygiene-and-beauty/hair-removal.

Whorton, James C 1993. The Phenolphthalein Follies: Purgation and the Pleasure Principle in the Early Twentieth Century. JSTOR. University of Wisconsin Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41111500?seq=1.